It was very surreal watching the proceedings of Westminster on 9th July. I had been napping, and after I received a message from my friends to watch it, I saw the tail end of the vote, a bellowing voice proclaimed ‘the ayes to the right 383, the nos to the left 73, the ayes have it’. I immediately rang my friends from Uni for clarification on what just happened and yes the unbelievable had just taken place. Equal marriage would be made law in Northern Ireland by October this year in the absence of Stormont. This was followed by a vote legalising abortion access. A truly historic day for Northern Ireland felt to have come out of nowhere.

It was not how I had imagined it to be. In my head, I had a vision that this day would be like the marriage referendum in the South, wherein the lead up there would be public debates highlighting issues facing LGBT+ people in the North and on the day, people would be out celebrating like at Dublin Castle, marking the historic achievement. I went out that night to Kremlin (Belfast’s main gay club) and spent the night in disbelief, so many people didn’t know about what had happened.

Ever since I moved to Northern Ireland from London in 2016, I had been aware that a possible route to achieving these human rights seemed like an enigma. Whether it was the DUPs ability to block reform through the infamous petition of concern in Stormont or Westminster’s lack of will to legislate for us Northerners labelling everything as a devolved matter, it often felt despairing being stuck in such a time warp with no one properly accountable. When I vented my frustration at fellow students during Freshers at Queen’s, I was often left with a response well this is Northern Ireland, a prevailing lack of hope in the political system to deliver for people.

Many times, I have felt akin to James from Derry Girls, completely perplexed by what is going on here. This would often happen when talking to fellow LGBT+ students. So many people had life experiences that deeply shocked me such as extreme homophobic bullying in school, schools teaching homophobia disguised as religious education or some of my friends being kicked out of their house by their parents after learning about their sexuality.

I began to understand the privileges I had taken for granted having gone to a school with a gay-straight alliance afterschool club where there were openly gay students and teachers and although I wasn’t out at school, I had role models and supportive parents for when I decided it was time. I had the privilege of hope when so many of my friends didn’t.

This feeling of inequality motivated me to get involved. Joining Amnesty International QUB introduced me to like-minded people who were fed up of the denial of human rights here in Northern Ireland and the effect it was having on LGBT+ people and women. Activism began to dominate my life, and through this, I learnt about the queer struggle in the North. Like many others before me, I attended countless rallies where the same chants were heard in the streets event after event, and despite the overwhelming support, nothing ever changed. At times it was despairing, especially when hopes about potential breakthroughs came and went.

July 9 was, however, that breakthrough. What appeared to be another glass bottle thrown at a brick wall was not. To the sceptic’s eye, however, the conditions attached to the bill in relation to if Stormont reconvened by October meant celebration was premature. But, even if Sinn Fein and the DUP made up (very, very unlikely) before then, this was about more than just the passing of equal marriage, this was about the hope of equality. So many of us plan to get away as being subjected to homophobia in the law, media, politics and society can get exhausting.

So often when talking to friends and family in the Republic or England, I talk about Northern Ireland as a lost cause under the grip of the homophobic, sectarian bigoted DUP but here was a chance to celebrate a promising beginning for proper LGBT+ equality. Hope has been topical in the light of the horrific murder of Lyra McKee.

Outside one of Belfast’s most glorious pubs, The Sunflower, her words ‘It won’t always be like this, it’s going to get better’ line the walls. In the wake of her tragic death, I will never forget Arlene Foster’s comment about how Lyra’s death doesn’t change anything about her party’s LGBT+ stance, thinking how insensitive and cruel that remark was at a time of grief.

Annoyingly, as long as the DUP and others keep homophobia in their manifestos, we will have to suffer the consequences. Although this day marked a hopeful turn, Northern Ireland still has a long way to go and us activist have a lot more fighting to do for it not to be such a cold house for LGBT+ citizens, but it’s official, we’re on route.

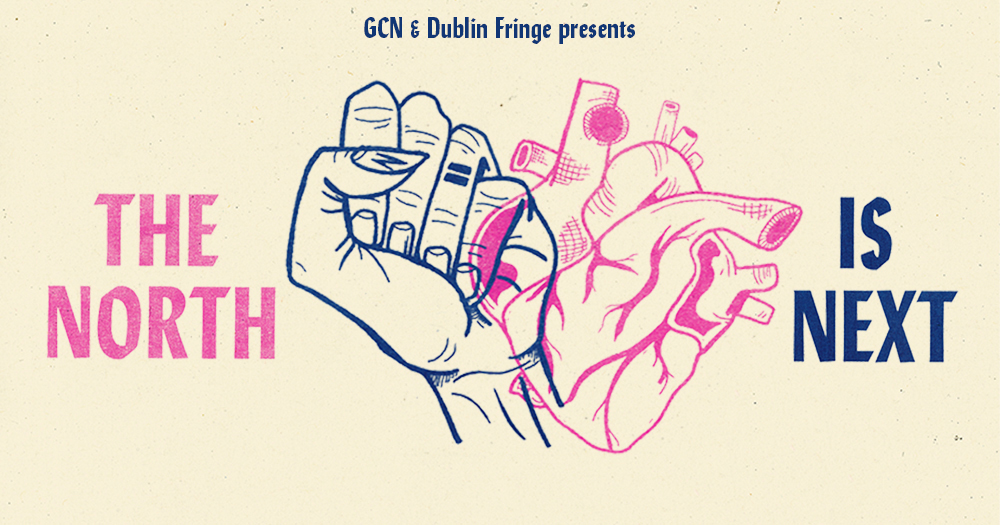

GCN has teamed up with Dublin Fringe Festival and Outburst Queer Arts Festival for an unmissable event about the fight for equal marriage and reproductive rights in Northern Ireland – The North Is Next. The event will feature performances, discussions and the launch of a bespoke zine publication produced especially for the occasion.

Visit the Dublin Fringe Festival website for tickets.

© 2019 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.