In August 1985 a Sunday Independent reporter, professing to be a confused 18 year-old, rang Tel-A-Friend to investigate the type of advice the service gave. Using the name Paul, the Sunday Independent reporter, took a detailed account of the conversation and reproduced it in the Sunday Independent on 25 August 1985.

The conversation revealed, perhaps to the disappointment of the undercover reporter, the extent to which Tel-A-Friend was a professional befriending and counselling service, not a service out to recruit or convert callers to homosexuality. The Tel-A-Friend volunteer, who Paul spoke to, simply sought to offer support and reassurance, insisting that ‘nobody chooses to be gay, for a start […] We’re not here trying to encourage people to be gay or otherwise’.

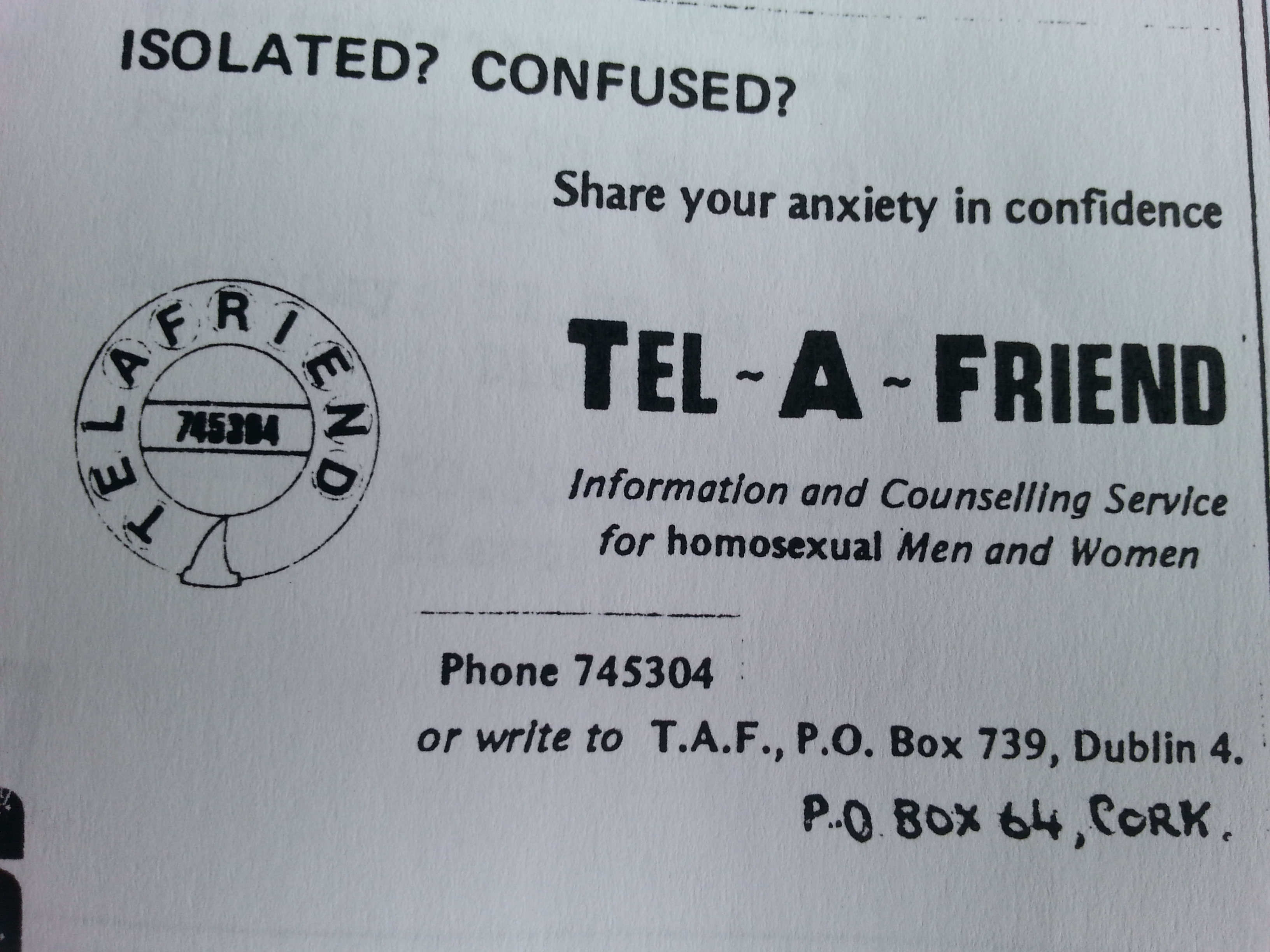

What is most interesting and revealing about this article, however, is not the fact that the Sunday Independent reporter rang Tel-A-Friend and the Sunday Independent printed the article, but the fact that the paper did not print the contact details of Tel-A-Friend for anyone who might want to contact the service. This article, incidentally, appeared in and around the same time that Tel-A-Friend had written to all the mainstream nationals requesting permission to place a regular advertisement for the service within their respective publications. The Irish Press Group was the only one to respond, refusing Tel-A-Friend’s request; the other national dailies did not respond. This was representative, however, of the lack of support Tel-A-Friend received from certain quarters, despite the important service it provided.

Tel-A-Friend was established in 1974 as the first confidential information and counselling service for homosexual men and women in the Republic of Ireland. From 1974 to 1978 it was housed at 48 Parnell Square, the premises of the Irish Gay Rights Movement (IGRM). In 1979, at the invitation of the National Gay Federation, following the IGRM’s loss of its Parnell Square venue, Tel-A-Friend moved to the Hirschfeld Centre, in Temple Bar, where it remained for the next ten years, becoming one of the most important initiatives of the gay rights movement in Ireland. A dedicated telephone befriending service for homosexuals was crucial at a time when the Samaritans reported that of the 180 calls it received from homosexuals in 1978, 20% were suicidal. The fact that these 180 callers called the Samaritans, rather than Tel-A-Friend, may well have been a result of the fact that Tel-A-Friend struggled to advertise its existence, with a number of publications refusing to do so, citing the 1861 and 1885 laws which criminalised sexual activity between males. Some rare exceptions included publications such as Hot Press and In Dublin.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, unlike its counterpart in Northern Ireland, Cara-Friend, which received a grant from the Department of Health and Social Services, Tel-A-Friend did not receive any state funding. In 1980 and 1985 Tel-A-Friend wrote to the Minister for Health and Social Welfare requesting funding because they provided ‘a social service to the public’. On both occasions, their requests were unsuccessful. That Tel-A-Friend’s request for funding was refused in 1985 in the midst of the emerging HIV/AIDS crisis demonstrates the extent to which the Irish state was willing to turn a blind eye to the struggles facing Irish LGBT+ individuals. In order to maintain the service, Tel-A-Friend had to fundraise or rely on funds provided by the National Gay Federation.

Tel-A-Friend adopted a strict protocol when dealing with callers. Those wanting to volunteer had to meet certain requirements and follow strict rules. In order to volunteer, one had to be homosexual but crucially had to be ‘totally at ease with their own gayness’. Once a call was received they had to adhere to the following guidelines: ‘Find out quickly where the person is phoning from; if they are ringing from a call-box ask if they have enough money for a long chat, and if warranted get their number and ring them back – but watch the time; ask fairly soon are you homosexual and mention that you are also; if the caller is not of your own sex, ask would you prefer to speak to a man (or a woman)?’.

As a befriending service, Tel-A-Friend also offered callers the opportunity to come and talk in person. Again there were strict rules in place. This was to protect the volunteers own safety and the wellbeing of the caller. Guidelines stipulated that ‘if a meeting is to be arranged specify that it is for a chat and that you and another or others will be there. Mention there can be no sexual contact between the caller and their befriender.’ These guidelines helped to ensure there was a clear understanding of the conditions around the meeting.

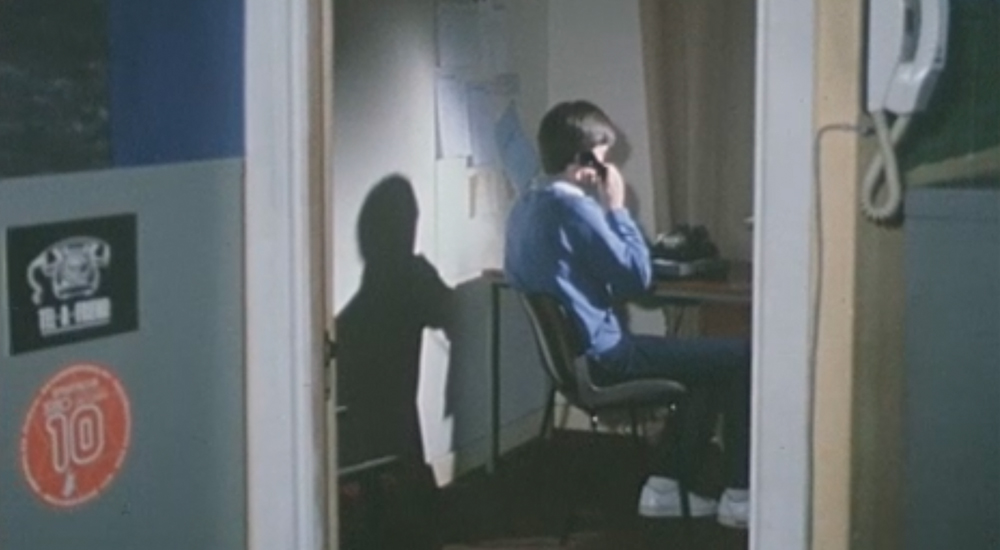

The types of calls Tel-A-Friend received were varied. Some simply contacted the service to find out where to meet other LGBT+ individuals or where the nearest gay pub was. Others, however, were from callers struggling to come to terms with their sexuality and who felt lonely and isolated. Don Donnelly, who volunteered with Tel-A-Friend in the 1980s, remembers that the most popular question asked by callers was ‘How would I know if I’m gay?’, while Des Fitzgerald remembers the nervousness of many callers he dealt with:

“It was very interesting for me because quite a lot of people were ringing from rural areas, from country areas. And they were really very isolated. They really didn’t have any place to go or any place to meet people, and very often you were the first person they talked to. So, we always operated on the principle that for the first 10 minutes they probably don’t hear a word you’re saying because they’re so wound up and nervous. So, the first part would be really calming people down and then just getting to talk to them.”

Worryingly, Tel-A-Friend revealed in 1985 that they had received calls from some individuals who ‘had even undergone psychiatric treatment as a result of shockingly bad advice given to them by some ignorant people, many of whom exist today giving that same advice’. To some gay activists, this might not have come as too much of a surprise. In February 1981, for example, Bernard Keogh had written to the Minister for Health, Dr Michael Woods, informing him that the National Gay Federation had been ‘made aware that numbers of homosexual men are admitted as patients to mental health institutions for “treatment” of their homosexual orientation’. There is much research to be carried out into the types of “treatments” some homosexuals were subjected to in the Republic of Ireland throughout the twentieth century. Only recently it was revealed that gay men were given electric shocks to “cure” homosexuality at Queens University Belfast in the 1960s.

For many individuals who contacted Tel-A-Friend, it was the first means by which they learned about homosexuality, about where to meet other gay and lesbians individuals, and learned how to come to terms with their sexual orientation. For many others, it was the means to become more actively involved in the gay rights movement in Ireland. It was through Tel-A-Friend, for example, that Kieran Rose first learned where to meet other homosexuals in Ireland. Rose recalled in a 2013 interview that:

“I remember arriving up into Dublin, getting my bedsit out in Rathgar, and got on to the Honda 50, went to a telephone box, which we had in those days and phoned gay switchboard (Tel-A-Friend), and then they told me about the IGRM in Parnell Square and that they had a cheese and wine [reception] on a Sunday, and that’s where I went and met gay people for the first time.”

Rose went on to become a leading figure in the gay rights movement in Ireland, helping to found the Cork Gay Collective in 1981 and later lobbying the Irish Congress of Trade Unions to support decriminalisation of sexual activity between males and rights for gay and lesbian workers. Rose was also instrumental in the establishment of the Gay and Lesbian Equality Network in 1988, which successfully lobbied for the decriminalisation of sexual activity between males in 1993.

Rose is just one of many thousands who came to the gay rights movement through Tel-A-Friend. Whereas in the period from 1975-76 Tel-A-Friend received 136 calls, this had increased to 3,703 calls in the period from 1985-86. The 1986 figure represented an increase of 625 calls on the previous year, part of which can be explained by the opening up of a second telephone line, but also an increased number of calls from those concerned about AIDS. Tel-A-Friend, however, had ensured that volunteers were prepared for such an increase by inviting Dr Derek Freedman, one of Ireland’s leading specialists in sexual health, and Gay Health Action to talk to Tel-A-Friend volunteers about AIDS.

Tel-A-Friend did not limit itself to the telephone line. Instead, it expanded some of its activities in an attempt to promote further gay rights and support services for the LGBT+ community in Ireland. In 1984, on foot of an increasing number of calls from transvestites/transsexuals, almost 270 in the period from 1984-85, Tel-A-Friend set up a TV group, which they advertised through In Dublin. The TV group met in the Hirschfeld Centre on a fortnightly basis. While Tel-A-Friend noted that the numbers who attended were small, they, nevertheless, felt it was a necessary step to assist ‘TVs to have a meeting place and an opportunity to get to know each other’. Tel-A-Friend also sought to reach out to the non-gay community to educate them on gay rights. In the period from 1984-85 members of Tel-A-Friend addressed seminarians at a meeting of the Jesuit Society of Philosophy, spoke to the Psychological Society in Trinity College Dublin, addressed a meeting of Marriage Guidance Counsellors and engaged with the Youth Switchboard of the Irish Family Planning Association, while also inviting the Samaritans to attend a Tel-A-Friend training seminar.

As noted earlier, however, it was not all smooth running for Tel-A-Friend. While they engaged in a number of activities and their services expanded, reflecting the demand for such services, it placed considerable financial pressure on the service, particularly when the Irish state refused to provide any funding. Moreover, Tel-A-Friend never had more than 20 volunteers at any one time, who on occasion were asked to make donations to support the service. Furthermore, just as Tel-A-Friend experienced its busiest year in 1986-87, with a total of 4,500 calls, a devastating fire at the Hirschfeld Centre in late 1987 left Tel-A-Friend without a home to operate at full capacity. It would not be until 1989 that Tel-A-Friend, which by then had rebranded itself as Gay Switchboard Dublin, found new premises at 13 Christchurch Place, thanks to Dublin Corporation’s Community Services Project. It is a testament to the grit and determination of those involved in Tel-A-Friend that the service was able to get back up and running again in 1989.

In the period from 1974 to 1989, Tel-A-Friend dealt with almost 30,000 calls. Interestingly, figures for 1989 showed a dramatic increase in calls from gay tourists from New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, USA, Canada, France, West Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Turkey, Italy, Spain, Wales, Scotland, England and Holland. Gay Switchboard Dublin estimated a 200% rise in gay tourists that year; a clear sign of the emerging pink economy in Ireland during this decade.

There can be no doubt that Tel-A-Friend’s legacy lives on in many of the support services which are now in existence for LGBT+ individuals in Ireland today. At a time when there were few other means for isolated, lonely and confused individuals to discuss their feelings about their identity or sexual orientation, Tel-A-Friend was a beacon of hope within a hostile social and political context. Those who volunteered behind the scenes provided a much-needed service, a service which the Irish state abdicated itself from providing. In many respects, Tel-A-Friend volunteers are the unsung heroes of the Irish gay rights movement of the 1970s and 1980s. One individual who might share this thought is Pauline O’Donnell who remembers the transformative effect ringing Tel-A-Friend had on her life:

“First of all”, she said, “well, we could meet you, say at the weekend or something. I think this was maybe a Wednesday night. And I said, is there any chance I could meet you tonight because having plucked up the courage to ring, I didn’t want to wait any longer, you know. I desperately needed to get my story out and to talk to someone of like mind. So, she said yes. So, Terri and the guy, some guy, came along with her and we met in the Royal Dublin and had a great old chat, and the relief was just unbelievable, to be able to speak honestly about how I felt. So, that was the beginning of a new life. I suppose for me really.”

© 2019 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.