“I take my great struggle, and my terrible suffering and pain, and I turn it into beauty for you. I get up on stage and you all find it beautiful.”

In 1991, AIDS activist and amateur filmmaker, Catherine Gund fled New York after a close friend died of the virus. Taking the camera she’d used to document ACT UP protests for the affinity activist organisation, DIVA (Damned Interfering Video Activist Television) TV, Gund ended up in Mexico, and there she found herself at a concert where a 72 year-old woman sang songs about love and loss with a voice that reached into the depths of her own suffering.

“I went to Mexico because I was drowning in grief,” Gund remembers. “And she was the first voice that came through to me. When somebody speaks to you like that, we can’t always put our reaction into words. I couldn’t have said I need to go to Mexico and find someone who sings beautiful songs, about grieving and loss and love. But I needed her.”

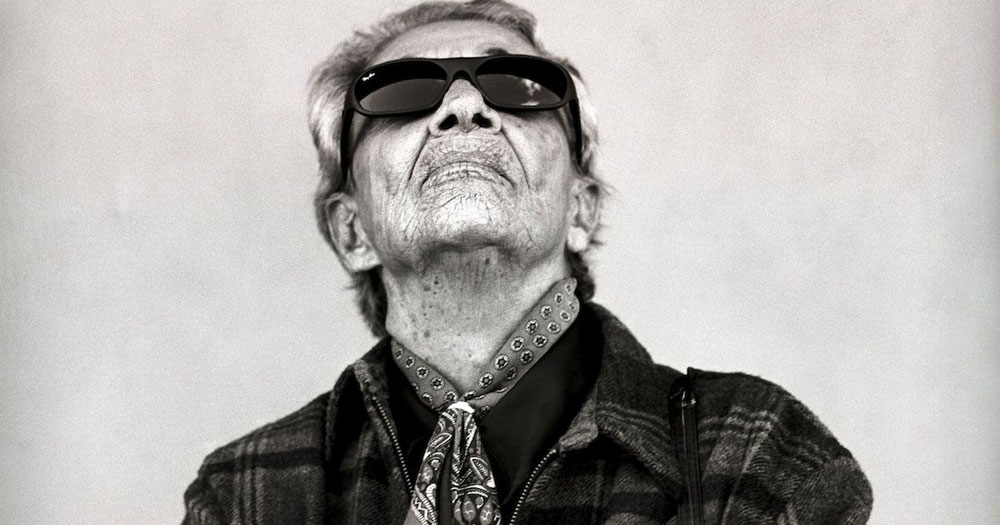

‘Her’ was the singer Chavela Vargas, who was then beginning the final flowering of a career that had defied both musical tradition and macho convention to see her become both lauded and dismissed, never quite taken seriously in her adopted home, while at the same time becoming a lover of Frida Kahlo and a member of the Mexican cultural elite of the 1960s.

After the concert, Gund asked Vargas if she could film an interview, and so began a story that comes full circle this year with the documentary film, Chavela, which Gund co-directed with Daresha Kyi.

Gund’s original footage, filmed at Vargas’ house in 1991, opens the documentary, with the young lesbian activist asking the older lesbian singer about her sexuality. “There was this sense about her of being a woman, and the joy she took in it was a very clearly a lesbian sense of love for women, and love about women. That was how I felt, because I walked in there and I was like, ‘So, Chavela, tell us about being a lesbian’. She replied: ‘I’m not a lesbian.’ And I was like, ‘wait, what?’

“Yet she talked very openly about a previous lover who was a woman, so there was no question that she was comfortable with who she was.”

The Heart of Chavela’s Appeal

This contradiction of being wholly visible as a lesbian, while at the same time not being out, was both the heart of Vargas’ appeal in her heyday, and the reason she was never quite able to deliver on the promise of that appeal. Having left her birthplace of Costa Rica aged 14 after a difficult childhood, she spent years singing on the streets before beginning to make her mark in live music venues with slowed down, hyper-emotional renditions of the Mexican rancheras that were popularised by singers like José Alfredo Jiménez in the 1950s and ’60s.

Early on in her rise to popularity, she dressed in the traditional feminine garb of Mexican women, but soon she ditched the fans and blouses for shirts and pants, dressing as a man, smoking and drinking with Jiménez, who became a good friend, and gaining a reputation as ‘the most macha of all the machos’.

“No matter how old we are, we cannot imagine what it was like in Mexico of the ’40s and ’50s for her to wear pants,” says Gund. “And if you look at the pictures, she is the only woman wearing pants.

“The other thing is that she didn’t change the pronouns in the songs. They’re all sung to women. So, for her as a woman, with her voice and the gravitas behind her sentiment, and her power, it changed the meaning of those songs. She took the music, which had this kind of very upbeat quality, and focused on the lyrics and turned it into what’s called music of the desperation of the wounded soul.”

The wealth of photographs and footage in Gund and Kyi’s film bear witness to an image that was both fearless and overtly, sexually lesbian. It was seen as exotic, but never given full credence.

“If someone asks what the documentray is about and I start saying all these things about Chavela, they sort of glaze over,” says Gund. “And then I say she was lovers with Frida Kahlo and they light up. Chavela had that same power as Frida, but she didn’t experience it in a positive way. She never felt that she had love.”

As Vargas style of singing and image began to fall out of favour, her drinking escalated. “She really suffered,” says Gund of Vargas’ extreme alcoholism. “She said, ‘I take my great struggle and my terrible suffering and pain and I turn it into beauty for you. I get up on stage and you all find it beautiful.”

Wilderness Years

The ’70s and ’80s were wilderness years for Vargas, her drinking affecting every area of her life. In her autobiography she describes the time as her “15 years in hell,” yet the women who loved her speak about a spitfire, drunken mess with almost poetic nostalgia. “It’s like the entire film is poetry,” says Gund. “The way that her lovers, friends and admirers speak about her comes out as rich and profound, and as motivational as the music that she shared.”

Around the time that Gund had her first and only interview with Vargas, she’d been rediscovered by women who ran a bohemian club in Mexico City, and was gaining a new kind of reputation, less about exotic ‘macha’ appeal, and more about the seriousness of her musical interpretations. She began to garner fans in Spain, and when in her late 70s she moved there, she found a new sense of herself.

“She was a celebrity which makes you much more isolated and surrounded by people who want something from you, people who have this superficial caring for you,” says Gund. “But the people in Spain loved her deeply, and they counted themselves as intimates or friends.”

Chief among those intimates was filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, for whom Vargas became a musical muse, her dramatic rancheras renditions becoming the soundtrack to films like High Heels and The Flower of My Secret. Grounded by the acceptance she found in Spain, she finally came out aged 81 in her aptly titled autobiography, And If You Want to Know about My Past. Two years later, Almodóvar facilitated her greatest dream, to perform at Carnegie Hall.

Vargas died in 2003, aged 93, and when the news of her passing emerged, Gund revisited her video recordings from 1991. It occurred to her that it was the only interview footage of Vargas talking extensively about her life, and so she began putting a documentary together.

“People have come up to me nonstop while we’ve been touring with this film saying, ‘you know history tried to bury her, and thank you for making this film’,” Gund says. “Because, whether they knew about her or not, nobody had ever put all of this together and put it out there. There are people in Mexico that had no idea what happened when she went to Spain. There are people in Spain, who have loved her music forever, who didn’t really know about her lesbian life. And there are people who knew she was a lesbian icon and had no idea that she went to Spain and hung out in this beautiful bohemian community.”

What comes across abundantly in Gund and Kyi’s film is the strength of Vargas’ personality, expressed through the songs she chose, which not only reflected her sexual identity but also told her life story.

“It was beyond magnetism and charisma, there’s a way that she creates desire in the people who hear her music and who met her,” says Gund. “I think we need her because we all experience love. And we all lose love, or we witness other people losing love. It is one of the most universal, profound experiences that humans can have. And that is what she chose to focus all of her life’s work on, helping us see that and feel it and understand it.”

Fittingly, but coincidentally, Chavela premiered at Outfest, the Los Angeles LGBT Film Festival on the birthday of the friend Gund lost to AIDS back in 1991. “It was completely by chance,” she says. “And I thought I should have dedicated it to him because it really is because of him that this film exists. If he hadn’t died, I wouldn’t have gone to Mexico.”

‘Chavela’ is at the IFI Documentary Festival this Friday, September 29 at 8.30pm, tickets available here.

© 2017 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

comments. Please sign in to comment.