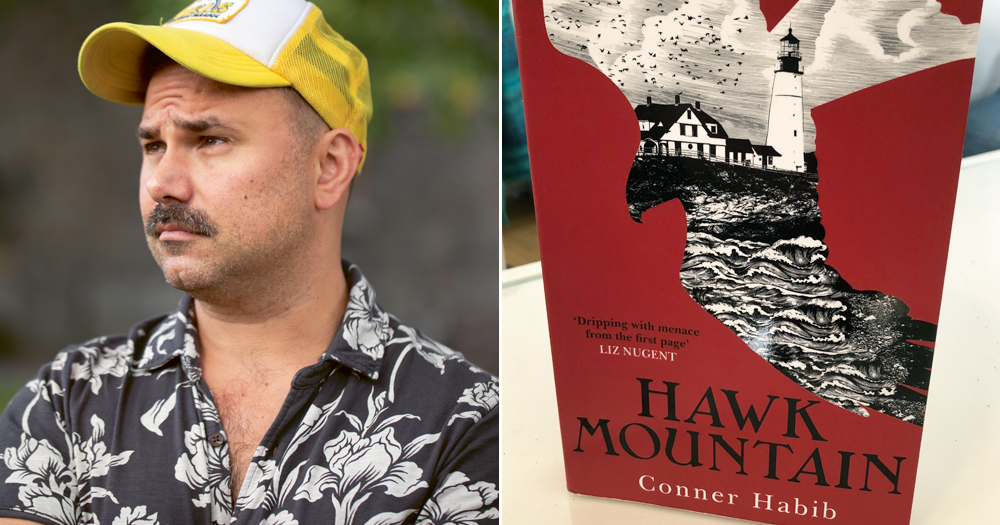

An absorbing read full of twisted tenderness and atmospheric tension, Hawk Mountain, the debut novel by Conner Habib, is utterly compelling.

“The boy looks up: green eyes, Todd sees. Like cracked sea glass. ‘Jack. Gates,’ Mrs. Call says again. ‘Not an easy name to forget. If you say it, you’ll remember it.’ She gestures to the class and they say his name in unison, except for Todd, who is caught off guard by these two syllables. Jack. Gates.”

From the first page of this compelling novel, the reader is drawn into a world both familiar and unfamiliar all at once. This masterful debut explores the darkest matter with a surprising and unnerving relatability and is a page-turner in the most classic sense. It made me feel on edge more than any novel in quite some time.

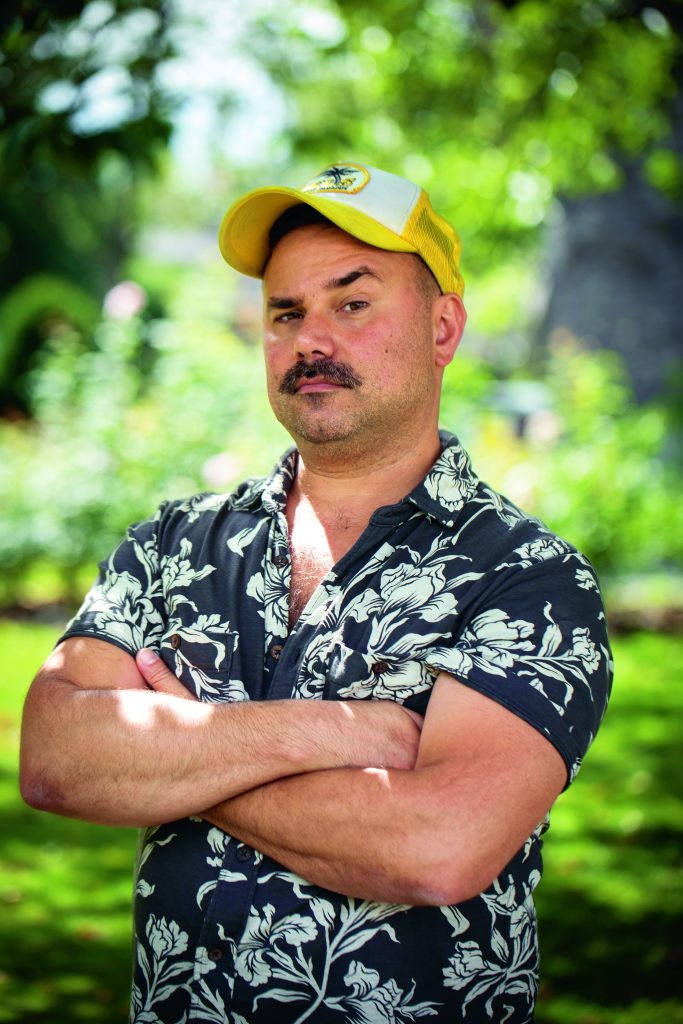

I had a chance to chat with the endlessly interesting author of Hawk Mountain Conner Habib to hear more about his journey to writing this novel, settling down to a new life in Ireland, the tyranny and trauma of our schooling systems and how our environments form our characters.

Conner moved to Ireland over three and a half years ago. He is a writer, lecturer and podcaster and now a novelist. His hugely popular podcast, Against Everyone with Conner Habib, is always guaranteed to make you think about things a little deeper and differently.

Irish author Liz Nugent aptly describes Hawk Mountain as “Dripping with menace from the first page,” and I have to agree. Habib expertly creates an atmosphere and momentum from very early in the novel that makes it unputdownable.

So, what is it about then, I hear you ask? Todd and Jack. Jack and Todd. Bully, victim, victim, bully. It’s a story of how two lives intersect and intertwine. Habib explains, “Hawk Mountain is the story of two men who haven’t seen each other since high school, reuniting on a beach by chance. Todd is at the beach with his six, almost seven year-old son. And he sees someone walking up. It’s Jack.

“After this chance encounter Jack kind of refuses to leave (Todd’s life and home) and he starts developing this really close relationship with Todd’s son, then something breaks, about a third of the way into the novel, something happens and everything spirals from there and becomes darker and darker and darker.”

The novel is written in a way that flicks from past to present as the story unfolds, revealing more and more of these men’s lives and connections. The past is its own character in a bigger sense as the novel meditates on how we process trauma across time and what those formative origin stories and experiences in our youth mean for us in adulthood. How they shape us. As LP Hartley wrote in his 1953 novel, The Go-Between; “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” How we understand the past and how we come to terms with our own memories is something all of us can relate to acutely.

The American high school setting and system loom large in the novel both in the present (Todd is now himself a school teacher) and in the past (Todd and Jack meet in school). Why did Habib choose school as a backdrop and location for a psychological horror?

“We tend to think of school as a place where bad things can happen, so we should mediate the bad things happening. But maybe school itself is actually bad. I don’t mean education is bad. I mean, this hierarchical system, that means you don’t get to see your family, every day for 12 years, where you’re expected to fit into social norms, mostly, which are leading you into training for a certain kind of workforce, or certain kind of labour, or stepping out of line and expressing yourself. Either that you get bullied, or you bully someone, or you fall into some sort of weird caricature or archetype. In the US, especially when you fall into these types of being a jock or being goth or being a skater kid, or whatever it is. So you get really streamlined into a process, it’s not yours, and because it’s very hard to experience, or express your individuality, or certainly to explore it.

“I think that that’s extremely claustrophobic, even if your experiences of school are good, or what we call good, it still has a really intense impact on people’s lives, in ways that they might not even know.

“So I think all of that is perfect to set the beginning of a horror story! But then, you know, most of the book takes place 15 years after high school. So it’s carrying all of that around. I know for me, I’m Syrian, and I’m gay, and I fall into all kinds of identities that could be considered to be marginalised. I’ve been in an abusive relationship However, actually, one of the most traumatic and difficult things for me was going to school. It was not because I was bullied, but because it was stifling because it was trying to control the way I think about and look at the world. And again, I mean, education itself is a gift and there are lots of good teachers and they’re probably good schools as well. But we shouldn’t overlook the way that it corrals people to a certain kind of existence for a really long time.”

Hawk Mountain first existed as a short story that Habib penned in graduate school. The characters and the story stayed with him and I was interested to know if he had a clear sense of what was going to happen to these characters in the novel?

“It definitely has changed from what it was to what it is now. I was really interested in melodrama. I was interested in Patricia Highsmith. I was really interested in even old Douglas Sirk movies, stuff like that. I thought ‘what can be more melodramatic than a thriller or suspense tale that’s actually a lot of melodrama?’

“I started to develop more of the pulse and the beating heart of the story, and it became a literary horror novel, but, you know, it’s not a horror story about a monster. It’s a horror story about emotional suffering.”

Habib has been living in Ireland for over three years now. What attracted him here and how has the move been from the US?

“I wanted to live here for most of my adult life. I came here when I was 15 with my family on vacation, and I’ve wanted to live here ever since. Then, I came to visit in 2016. And that was the sort of reaffirmation. And, it’s been great.

“I think for me, it’s just such a difference. It’s such a different culture, no matter how much overlap there is. It’s very much its own thing, people talk to their neighbours, and they have long chats with each other – a kind of slow and loose aspect that does not exist in most of the places I’ve lived in the US. I think that it’s something that can be overlooked when you live here. And it’s also something that can infuriate people here sometimes too, but it’s actually really lovely coming from the US. Seeing that kind of togetherness.

“You know, living here during the lockdowns, even though the lockdowns were much stricter and longer here than they were almost anywhere in the US, I was so happy to be here. Because of the cultural conversation, the US would have been absolutely unbearable for me, people were just at each other’s throats. And it just wasn’t like that here. The atmosphere here was much more a sense of solidarity with one another. So I’m very fortunate to be here.”

Habib and I inevitably ended up investigating identity in the context of writing during our conversation. He shared a revelation he came to after an event he attended in which authors Torrey Peters and Mona Eltahawy were in conversation with Una Mullally. Peters explained that she wrote her bestseller Detransition, Baby for other Trans women. Conner expands, “It helped me realise the way in which writers who have any sort of marginalised identity are always asked to write about their identities. And so in some ways, writers, and I’ll include LGBTQ+ writers, are never allowed to write fiction. Because it’s turned into nonfiction.

“You know queer life or this is about what it’s like to come out, or whatever. And I appreciate all those, there are lots of books like that, that I really love. However, they’re often curated by non-queer people but it makes me wonder how many creative artists get swept under the carpet, because they’re not willing to turn their art into an educational role for straight people, cis people, white people, etc.

“The thing with this book is that I’ve had to try to keep it as – this is a story, this is a novel – and anybody who wants to come and read identity into it, that’s awesome.”

Hawk Mountain by Conner Habib is now available online and in all good bookstores.

This interview originally appeared in GCN Issue 373, which you can read in full here.

© 2022 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

This article was published in the print edition Issue No. 373 (August 19, 2022). Click here to read it now.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.