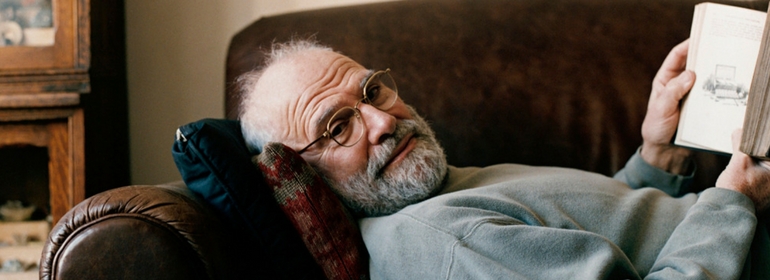

A new memoir by photographer Bill Hayes charts his relationship with the legendary psychologist Oliver Sacks, who at the age 76 fell in love for the first time, before passing away six years later. It’s a book that finds humour amid grief, the author tells Jarlath Gregory.

I’m not quite sure what to expect when I arrive at the hotel to meet Bill Hayes. From his memoir, I know that he’s American, older, and not very tall, but which Bill Hayes will I meet? The erudite journalist and author with a love of art and culture, the streetwise photographer whose Polaroids intersperse the narrative of his new book, or the chatty conversationalist who captured the heart of one of the foremost popular psychologists of our time? I find a dapper, charming, middle-aged man with a twinkle in his eye, unfazed by finding himself at the end of a promotional tour of major European capitals, equally happy to discuss the grief at the heart of his memoir, ask where to find the best gay bars in town, or break off mid-interview to help the flustered waiter replace our chairs.

Bill Hayes was recovering from the loss of his partner, Steve, when he moved to New York at the age of 48, with only the vaguest plan of how to get by. In the memoir Insomniac City, he recounts his everyday adventures in the city, but also charts his unexpected relationship with the well-known neuroscientist, Oliver Sacks, author of bestselling psychology books The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Musicophilia. There is humour and pathos in the memoir, as the reader is drawn into Bill’s romance with an older man who has been closeted and celibate for decades. As Bill says of Oliver in the book: “He was without a doubt the most unusual person I had ever known, and before long I found myself not just falling in love with O; it was something more, something I had never experienced before. I adored him.”

Insomniac City reads as a love letter to New York City as well as a love story about you and Oliver. Can you explain how you and Oliver came to meet?

Nine years ago, when I was living in San Francisco, I got a letter in the mail, hand-written from Oliver Sacks. Of course, I knew his work. In the letter, he told me he’d read my book The Anatomist, which had come out a few months before. It’s about Gray’s Anatomy, the classic medical text, and he simply wrote to say he’d enjoyed it. It was a very cordial letter. I was surprised and flattered of course, and I wrote a letter back. He wrote a letter back to me, and we had a little correspondence.

On a trip to New York we had lunch together, and it was very collegial, though there was a certain spark. Fast-forward a year later, I made the move to New York City. This did not have to do with Oliver. I’d had been living in San Francisco 25 years. I’d had a partner of 17 years who had HIV/Aids, but had been saved by medication. I say all this because it came as a complete surprise when he died unexpectedly one morning of a heart attack at 43. It was shattering and traumatic. It took time to get re- grounded and ready to move forward.

I didn’t know very many people and once I moved to New York, and Oliver and I started seeing each other, at first as colleagues and friends, but very quickly it turned into a romance. Insomniac City is about New York, which in many ways is the main character in the book, and my relationship with Oliver up until his death in August 2015. It’s also about my reinvention of myself as a photographer. I bought a camera right before I moved and was drawn to taking photographs of people on the street.

It’s also about this eminent figure, Oliver Sacks, finding love and coming out later in life. That’s a fairly unusual story in terms of what we’re used to in popular culture.

I do think it’s unusual. Since the release of my book in the US, one of the remarkable things for me has been the engagement with readers, particularly through social media, which has changed since my last book was published. I have heard from a couple of older men who told me they came out in late age. In fact, a couple days ago I heard from a man in his early 70s who’d been married twice, the last time for 37 years, and had just came out to his entire family after his wife died of Alzheimer’s. He found great inspiration in the book.

At one point, you express your surprise that a 22-year-old man has a husband. Do you find yourself surprised by how far gay rights have come, or more surprised that young gay people want to settle down?

Both, really. I am surprised by how far it’s come. I didn’t envision what we have. When I was with Steve in San Francisco it was a very big deal when domestic partnerships were made legal. We went to City Hall and got a domestic partnership, but it was definitely a step below marriage.

I am surprised how much younger gay men embrace marriage. It’s not something I’m opposed to in any way; it’s just not part of my thinking. I’m from a different generation, I guess. It’s often marriage with monogamy and following a different norm from the one I thought of as being part of gay culture.

At first you were amazed that Oliver lived a celibate life for a long time before you met. Do you think that’s indicative of Oliver as an individual, or more indicative of a man of his age and background?

He was very shy and not one to go out to bars. As Oliver wrote in his autobiography, he knew he was gay as a teenager and came out to his parents at 18, I think. He was raised in a very traditional Jewish household. His mother especially was horrified and essentially cursed him, saying, ‘You are an abomination,’ and wished he’d never been born. This was very scarring for him.

He did have some early trysts and romances, had his heart broken, but then essentially closed that door. He devoted his life to his practice, his patients, and of course his amazing books. He lived a very solitary life, almost a monk-like existence. He never expected to fall in love, never expected to have a relationship. But as chance would have it, we met. There were some challenges in the beginning because he was not out and he was a public figure, whereas I had come out at 24, moved to San Francisco in 1985, written about being gay, had lived my entire life as an out gay man. That got easier over time.

Although the book is often very sad, there’s a lot of yearning, hope and happiness in it too. In contrast to the image of a young woman reading a self-help book on the subway in the book, do you think Insomniac City offers philosophical advice on how to live well?

I think so. I would hope so. The memoir is book- ended with two traumatic experiences. It opens with Steve’s death and closes with Oliver’s death, and yet I don’t think it’s a book about grief. Both death and grief and loss are part of life as I understand it. I moved to San Francisco in 1985, into a flat in the Castro, right as the Aids epidemic was exploding. I saw and helped many friends who died or became sick at young ages. It was such a different time. So scary. But death as part of life became part of my understanding of what it is to live. The focus on life and openness to living in this book is how I’ve lived my whole life, especially since Steve’s death. The openness I show to my neighbours, however different they might be, whether it’s Ali at the smoke shop, or a go-go boy, or a very elderly woman, is something I hope people can find inspiring – that one can connect with one’s neighbours, or speak up for those who might not have a voice.

You wrote the book shortly after Oliver’s death. Did it offer some sort of closure for your grief?

I’m often asked if it was cathartic to write the book, and to me, the word cathartic suggests that the grief is erased, and it hasn’t done that. I still think about him a lot. I miss him a lot. But there is something unifying about writing the book and making something beautiful out of it. I very much wanted to make a beautiful book, one that had the funny and comic and playful parts of our life, as well as the sad, for the reader to smile and chuckle as well as shed a tear.

My life with Oliver was so much fun. He was essentially such a cheerful person, almost boyishly curious about the world. I wanted to capture that and give a feeling for what life in New York City is like – the photographs of people coming and going is meant to give a sense of what it feels like to live there.

Would Oliver like to be remembered, and if so, how?

I think absolutely, and I think he is remembered and beloved, and would have been had I wrote this memoir or not. Because of his amazing legacy of expanding our notions of neurodiversity, recognising, identifying, empathising with conditions like autism, Tourette’s, Parkinson’s, savant syndromes,all the things he explored – blindness, colour blindness, the culture of the deaf, that humanity. He was certainly beloved and lot of that love has come my way since his death, which is lovely. I also hoped to capture his playfulness and his brilliance. I couldn’t help but be struck by the brilliant things that came out of his mouth. I kept a journal of that even before we became involved, and I kept that journal up until his death.

Any plans for the future?

Right now I’m completing my next book, which is a book solely of my street photography. It will be out early next year. The new book will be both black and white and colour, it’ll have a little bit of text, sort of the inverse of Insomniac City – it’ll have its own narrative, like a dreamy walk through Manhattan without regard to time or season, and it’s called How New York Breaks Your Heart. I’ll do another book after that, a history of exercise called Sweat, which will be more like my previous books – a history with personal memoir. I’m very excited about it.

Insomniac City is published by Bloomsbury, €16.89

© 2017 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.