In post Marriage Referendum Ireland, LGBT+ issues are no longer discussed in hushed tones, and the likelihood of someone knowing an LGBT+ person in their family has increased tenfold.

In fact, a huge part of the campaign for Yes saw activists reach out to their families to have frank conversations about how a Yes vote would affect them. The hashtag #RingYourGranny caught on like wildfire.

For many LGBT+ people, this was a turning point: To ensure equality in civil marriage, they had to make their lives, and the lives of their friends, the focal point of conversation. They had to tell people, ‘This is about me’. Some had never had to do that with their parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles before.

The stories of LGBT+ people and their families (biological or otherwise) have been documented in everything from books and TV to YouTube videos and podcasts.

However, it’s rare to hear stories from LGBT+ people who grew up with LGBT+ siblings. How do their stories differ from the expected narrative?

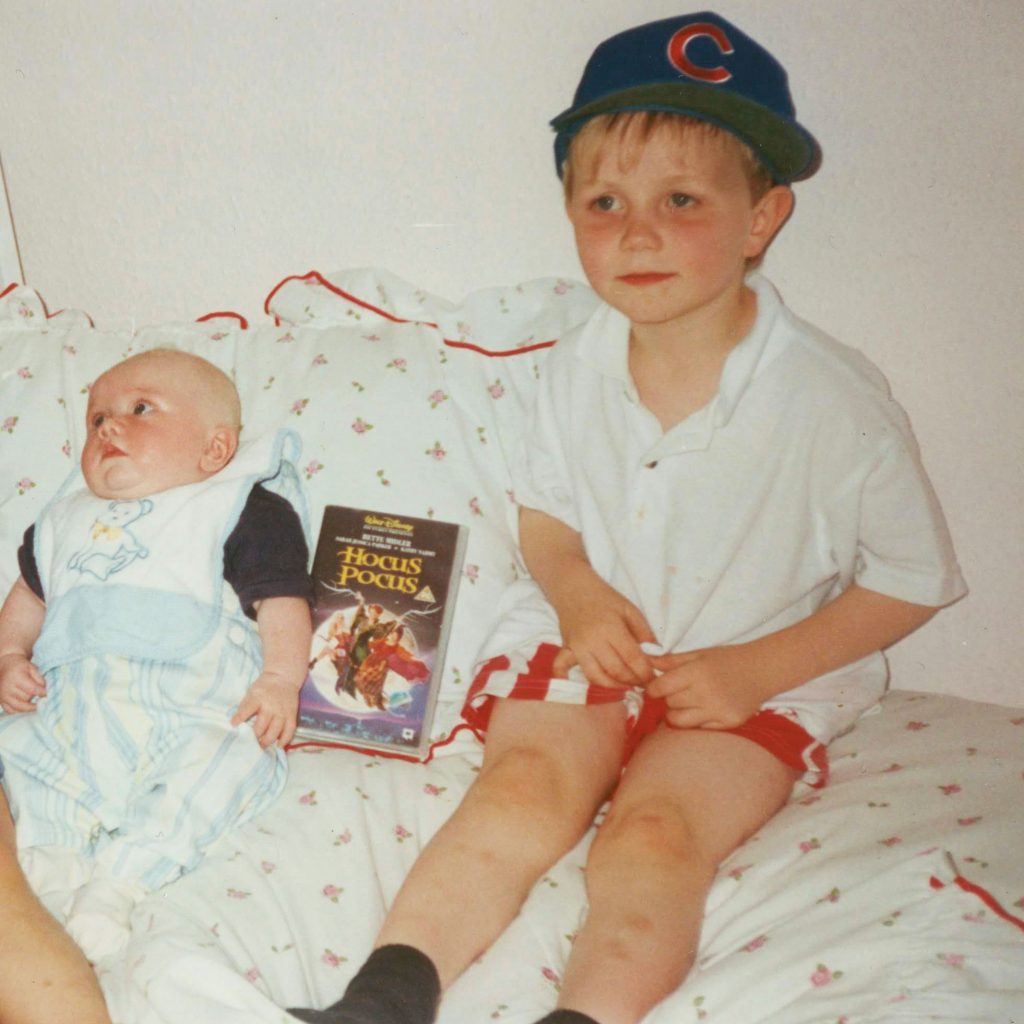

Luke and Declan Faulkner

At first glance, Luke and Declan Faulkner are very similar: They are funny, eccentric, and expressive. Sitting in a café in Rathmines, they bounce off each other rapid-fire like a queer comedic duo and seem to have a common understanding of each other’s personality quirks.

This was not always the case, as Declan informs me: “[Growing up], I didn’t really like Luke and he didn’t really like me either.”

According to Luke, this was due to the pair’s age gap: “My sister is two years younger than me, and Declan is five years older. When you’re a child, there’s a bigger age gap. Me and [my sister] were loud and annoying.”

Maturity is one reason for their newfound rapport. Another links the two in a bigger way. “I didn’t come out until I was 18, even to myself,” Declan says. “I could even pick the date on the calendar where I said it to myself.”

“I came out to myself, and then Declan came out,” Luke says. “And I was like, ‘oh I’m going back into the closet now’ [because] I felt like there can’t be two […] Then around 15 or 16 I went, ‘ah, no’.”

While Luke had no qualms about acting ‘different’ with his family and in school – by way of having a friend circle exclusively comprised of girls – Declan felt a larger pressure to conform to the norm. “I was more sociopathic. You have all these coping mechanisms to get you through, to avoid the shame.” He continues, “When [Luke] was a child, I would say that he didn’t like football, and we lived in a little GAA suburb, and that’s as good as saying, ‘I want to murder 10 million people. [He] didn’t really care about social suicide, whereas I was like, ‘what tools have I got to get through this’?”

“Declan said that I was in the closet with the door open,” says Luke.

The pair’s watershed moment came when Declan threw a house party while their parents were away. Luke had just turned 18 and was finally allowed to stay up with his brother.

Declan recalls, “I asked you if you were bisexual because I thought that might be a way to get you to open up, just to confirm it, even though I knew. It was up to me to open that dialogue.”

Once the brothers had both come out, it began to feel like their family came closer together.

“That was when the family could really begin,” Declan says. “It felt like this tiny little drawer that needed to be pulled open.”

Luke elaborates: “It’s a lot more united.”

Although Declan has always felt a degree of responsibility towards his younger brother, he always knew that he would be okay: “It was clear that he was mature enough. I admire him.”

Mike and Naoise Dolan

In their youth, brother and sister Mike and Naoise Dolan had a nebulous sense of feeling different.

“The earliest signs of non-straightness were kind of on the gender-conforming side of things,” Naoise says. “Not so much wanting to do traditionally coded masculine things as not wanting to do traditionally coded feminine things.”

Mike agrees: “Where it would be different for LGBT+ siblings growing up who are the same gender, for us it was experiencing gender variants towards the other person’s direction. I think, to go back into that mindset, there may have been some latent jealousy that Naoise was able to access forms of experience and expression that I wasn’t able to.”

Naoise came out in her third year of college, when Mike, who still hadn’t told his family, was in his sixth year of secondary school.

“Naoise just randomly slipped it into the conversation, like, ‘oh, by the way, I’m gay,’ and just kind of moved on,” he remembers.

“It was a very disarming moment because obviously, in my mind, I had coded my story as being ‘the only one’ and feeling isolated, so it was really strange to discover that, not only was there one other one I knew, but they live in the same house and are my sister.”

Although Naoise’s coming out paved a path that Mike would soon follow, he says the five years between him realising he was gay and Naoise opening up about her sexuality still weighed on him. “I think a lot of the damage tends to be done when you’re a lot younger,” he says. “And I was still in a secondary school environment that was no longer as actively homophobic as it used to be, but was still a place where I did not feel comfortable sharing that about myself.”

Naoise attended the same school as Mike and outlines the difference a few years can make. “It was a mixed school, and even in the three or four years above mine it was still actively homophobic then. I feel like it has changed pretty precipitously in that sense.”

Mike and Naoise, self-defined private people, have never shared a watershed moment where they addressed both of them being LGBT+. “We had a lot of the same friends in college, so he just never needed to come out to me,” Naoise says.

“I think we just started talking about it without realising,” Mike elaborates. “I think we started talking about the cultural aspects of our identities more… so it was probably something about RuPaul’s Drag Race.”

When asked if both of them being LGBT+ has brought them closer together, she responds almost instantly with an enthusiastic – “Definitely.”

Mike continues: “I definitely feel like it’s something that’s a defining feature of my personality. If it wasn’t something we were able to discuss at all, that neither of us knew about each other.“

“It would just feel insane,” Naoise interjects.

Maria McGrath

Maria McGrath is currently working towards a degree in Creative Music Production in NCAD. She is originally from Galway. She is LGBT+ and older than her sister, who is bisexual.

“We’re very lucky to have a father who does not give a fuck as long as we don’t kill someone. He’s very vocal on his belief that you should not be homophobic, he is very vocal on his belief in gay marriage. He has never given me a reason to think he would never accept my sister or accept me.”

When Maria was a teenager, her mother passed away. Her sister was 10. “I don’t want to say I was a mother to her,” Maria says. “It was more so that I had to parent her a little bit more.” She did not feel concerned about her family knowing her sister was bi: “I don’t think either of us experienced homophobia in the way that other people do if they’d grown up in a conservative family.”

Although only five years older, she has noticed striking differences between her coming out experience and that of her sister’s: “When I came out, I was rejected, and I had people who said, ‘I don’t want to be your friend.’ By the time she came out, the referendum had passed, Glee was on.”

Kate Butler

Kate Butler is 25. She grew up on a farm in rural Roscommon. She is the middle child of three and currently works in Dublin. Kate is younger than her brother, who is gay.

“I came out as gay to my parents on Saturday, October 11, 2014,” says Kate. “I only realised after the fact that this is National Coming Out Day. They were very open minded and my mam does a lot of work with and around LGBT+ young people.”

She continues: “I was still insanely nervous, as I think most people are, because even when you know your parents haven’t a problem with these things, you are kind of challenging the idea of your future that they had in their head and sometimes

I think that can be the part some parents struggle with.”

Kate, who came out before her brother, feels her open minded family environment may have eased the pressure on her sibling. “In a way I can imagine that it made it a little easier for him because he could see that our parents would be okay with it; but, I’m sure he still had his own concerns. My parents were always going to support us no matter what [but] he was experiencing it as the eldest and only boy in our family, and there are underlying societal expectations for boys in rural Ireland.

“Growing up he carried more of the stereotypes of being gay whereas I think I was kind of lucky because I coasted along in the background and I got to work everything out for myself in my own time. I think there was a lot more pressure for him.

“I think sometimes people think that because you’re born gay you always know you’re gay but it’s hardly ever that easy and it can make the coming out process very difficult when people are pushing their own opinions and expectations on you.”

This story was originally published in GCN’s Pride Issue 355.

© 2019 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.