With over 200 days that Debenhams workers have been forced to fight for their redundancy packages, Orla Keaveney joined the picket at the Henry Street store for an evening shift. They spoke to the workers and their supporters about their experiences, learning of the importance of solidarity, and why other marginalised groups, including the LGBTQ+ community, will be impacted by the outcome of this action.

Just before Easter, Debenhams workers were assured by head office that their jobs would be safe during the COVID-19 lockdown. The next day, they all received the same, impersonal mass email informing them that the Irish branch of the company was going into liquidation and they had been made redundant. Despite having little to no activism experience, these workers, many among them women who had spent decades working for the multinational retailer, scrambled to salvage the redundancy packages they had been promised.

At first, they were optimistic that they would be soon given what they were contractually owed: two weeks pay per year of service from Debenhams, on top of statutory redundancy. Some of the workers had even joined Debenhams from Clerys after its sudden closure in 2015 and the gruelling liquidation process that followed, and hoped that history would not repeat itself. However, after over 200 days, little progress has been made.

Debenhams protesters will be 200 days picketing tomorrow. They want two weeks statutory redundancy plus two weeks pay for each year worked.

Demonstrators have previously told me “we’ll eat our Christmas dinner on the loading bay” if it comes to it. https://t.co/6pXo9WEE3a

— Hannah Murphy (@hanelizamurphy) October 25, 2020

The only bargaining chip that the workers have is the stock that remains in the Debenhams stores nationwide. While estimated value of these unsold products isn’t certain, documentation retrieved from the shops leads workers to believe the total stock in Ireland is valued at around €30 million, accounting for price drops for seasonal goods. Just €13.5 million would be needed to give all of the Debenhams workers their full redundancy packages, but the liquidators, KPMG, have refused to commit to this figure. So the workers have no choice but to guard the abandoned shop premises 24/7 and block the liquidators from retrieving the stock.

I joined the Henry Street picket at 5pm on a chilly October evening. I’d followed the story from afar over the past six months, but had only passed the picket the odd time. While I had sympathy for the plight of the workers, I didn’t think there was anything tangible I could do to support them until my friend Sadhbh Mac Lochlainn, a PBP activist (and fellow bisexual), explained how the picket worked and welcomed me to join her on a shift. So I cycled down to the Ilac Centre on Parnell Street, to offer my time.

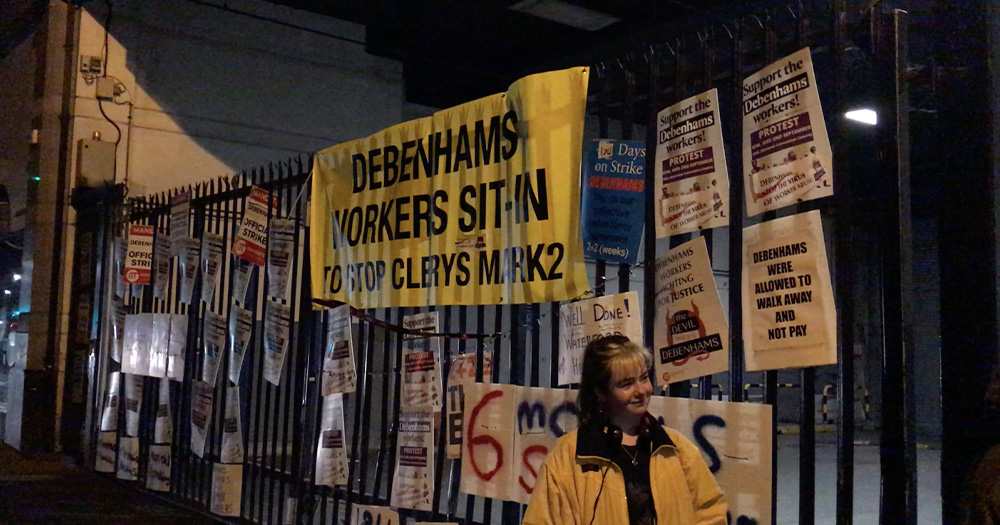

Each day is divided into four six-hour shifts, including a particularly tough midnight-to-six am one. At least two people must be on guard at all times to prevent KPMG’s lorries from entering through the loading bay and removing the stock inside the shop. As I pass through the ten-foot gates covered in posters about the workers, I see six picketers sitting in a circle of evenly-distanced camping chairs, shielded somewhat by a windbreaker. I wave to Sadhbh and introduce myself to the group as someone pulls up a chair for me.

The picketers have clearly spent countless hours together over the past six months, and have developed a bond despite the wide range of ages and backgrounds. Watching them pass around a box of Quality Street and tease each other affectionately, it almost feels like a family at Christmas, though instead of a cosy sitting room we’re gathered in a draughty concrete hollow as traffic roars past. At first, I feel a bit out of place but once I get to know everyone, I join in on the conversation about Netflix recommendations and weekend plans. Every so often we’re interrupted by a loud beeping sound as the loading bay opens to let a car in or out, or someone has to get up to reactivate the sensors for the automatic lights.

Eventually, Jane and Wes, both former Debenhams workers, get up to do a sweep of the shop entrances, and I offer to join them. Every hour, someone from the picket has to check points of entry into the Debenhams store in case KPMG make another attempt to take the stock. Most of the entrances have been chained shut – “to slow them down”, Jane tells me. She describes all the ways that the liquidators have tried to cross the picket, such as pretending that they are with Dunnes Stores in order to get past. The workers need to be constantly vigilant: if the stock is taken from the shops, they will lose the only power they have left in the negotiations.

Back in the loading bay, I’m told of how by-passers often show their support by bringing the picketers snacks, a fiver for hot drinks, or even home-baked food. Jane fondly mentions a woman called Gloria who always brings a box of sweets after her weekly shop in the Aldi next to the loading bay. It’s clear how much these little gestures mean to the picketers, keeping spirits high despite the crushing fear that they will never see the redundancy packages they deserve.

Debenhams workers 200 days on the picket line ✊✊❤️❤️?? pic.twitter.com/zS1pvXDTna

— karen gearon (@karen_gearon) October 26, 2020

At 6pm, the people for the late shift begin to arrive and I re-do my introductions. It’s interesting to see the different habits of the various picketers: one ex-Debenhams worker, Conor, brings a free toy from McDonalds and adds it to the long line on top of the wall, each corresponding to a six-hour shift he’s spent in the loading bay. Summer, from the Socialist Party, tells me that this is her eighth evening in a row here – she worked in a pub before the pandemic, so she’s used to being busy late in the evening. Fiona shares that she’s applied for a PhD, which somehow evolves into a discussion of our favourite art galleries in Dublin. Lorraine later joins with her dog Strongbow, who spots me as a newcomer and gives my shoes and sound equipment a thorough sniff. Despite the grim reason that brings such a varied group together, it’s nice to spend time with decent, compassionate people.

I record a one-on-one interview with Carmel Redmond, who worked as a sales advisor and then stock supervisor for Debenhams since they first came to Ireland in 1996, until her employment came to an abrupt end. The Wednesday before Easter, Debenhams called her in to help pack up Easter eggs and other goods, supposedly for charity – which struck Carmel as odd.

An email from head office that evening told them not to worry about their jobs as “there was only a situation in the UK”. But the next day, Carmel returned home from a walk to see several missed calls from her friends and colleagues. She learned, from the generic email that nearly 1000 workers across Ireland received, that the Debenhams were not going to reopen in Ireland, and was simply told to check gov.ie for more information. “That was it, after 24 years.”

Mandate calls for “definitive action” from Taoiseach to end Debenhams dispute after workers mark 200 days on strike – #debenhams https://t.co/4Z4ObBSlt2

— Mandate Trade Union (@MandateTU) October 26, 2020

As liquidators, KPMG are paid to divide up Debenhams’ assets between any creditors the company owed money to. While this includes the workers, they’re “at the bottom of the list”, and will only be compensated after KPMG, Revenue, the concessions within the department store, and vulture funds have all taken their cut. This could leave hundreds of workers with as little as €2 million to divide between them, a fraction of the redundancy packages that they were promised in their contracts. The workers, relying on the now-reduced PUP, are in an incredibly vulnerable position: “People are in a right mess, [struggling to pay] bills, mortgages… it’s scary.”

In the days following that devastating email, the shell-shocked workers formed a WhatsApp group to organise their first picket, which the Gardaí “aggressively broke up… treating us like criminals”. In a way, Carmel is grateful for this hostile reaction as it helped bring their situation to the attention of workers’ rights groups across Ireland: “We started getting contacted by People Before Profit, the Socialist Party, people who really cared – it’s unbelievable how much they really cared.” These organisations provided additional picketers, printed weatherproof posters, and kept the workers’ plight relevant in the Dáil and national media.

The support of the public has also been hugely appreciated. Carmel was especially touched that homeless people have cheered the picketers on, “telling us ‘Give them hell!’…one woman even put our placards on her tent… it’s very humbling.” The support goes both ways – on one night shift, a distraught father passed the loading bay with a photo of his missing son, whom he feared was struggling with substance abuse. The picketers recognised him as a young man who had stopped by the day before looking for food and water, mentioning that he was sleeping rough in Phoenix Park. “We told him, ‘If he was met with kindness here, he’ll come back here.’” The following morning, the young man returned, and the picketers helped reunite him with his father. “He got in touch with us [afterwards] and said he’d gone back to college and had gotten some help… we were so thrilled about that.”

Incredible work – @debenhamsstaff in Ireland have been on strike for 200 days: https://t.co/vtwESn9h0j

— The Poisonous Euros Atmosphere Fan (@DawnHFoster) October 26, 2020

Moments like this have helped boost the morale of the workers, especially as the weather gets colder with no end to the loading bay shifts in sight. Hearing Carmel’s story, and seeing the difference that even a small sign of support can make, I resolve to come down for a shift once a week to help ease the burden on seasoned picketers. One of my favourite movies, Pride, follows the true story of LGSM, a group of lesbians and gay men that fundraised for Welsh miners during the 1984 strikes. As a queer person, this picket feels like an appropriate way to honour my community’s history of solidarity with other marginalised groups.

And as Sadhbh points out to me, LGBTQ+ people are more likely to be in precarious working conditions; less likely to have family support systems to fall back on; and also more vulnerable to workplace discrimination. Allowing Debenhams to mistreat its employees like this paves the way for future abuses of our hard-earned protections. The fight for workers’ rights is intrinsically linked to the well-being and safety of our community.

The end-goal of the Debenhams workers is for the recommendations of the Duffy Cahill Report, commissioned following the Clerys closure to protect employees, to finally be brought into law, and for its protections to be extended to them. Until then, 24/7 shifts in the loading bay will continue. KPMG have recently gone to the courts looking for an injunction, meaning picketers could be arrested if they interfere directly with stock removal – a sacrifice that is not expected of all of the picketers, but that some feel they will need to make.

At the end of my shift, the picketers remained cheerful as they waved me off. However, I was saddened to imagine the long, cold night – and the even longer months – ahead of them.

© 2020 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.

comments. Please sign in to comment.