As we celebrate Pride Month across this island, we must confront the harsh reality that our community faces a rising tide of disinformation, scapegoating and hate. It’s time again for us to channel our collective pain and anger into action for social justice. As part of the #StrongerTogether initiative in collaboration with the Rowan Trust and the Hope and Courage collective, GCN interviewed Diego Caixeta of the MPOWER programme, who spoke about how Ireland can learn from the rise of the far-right in Brazil if it takes action now.

As Ireland’s growing far-right movement continues to put the lives of refugees, minorities and the LGBTQ+ community at risk, it’s important to contextualise the violence from a global perspective.

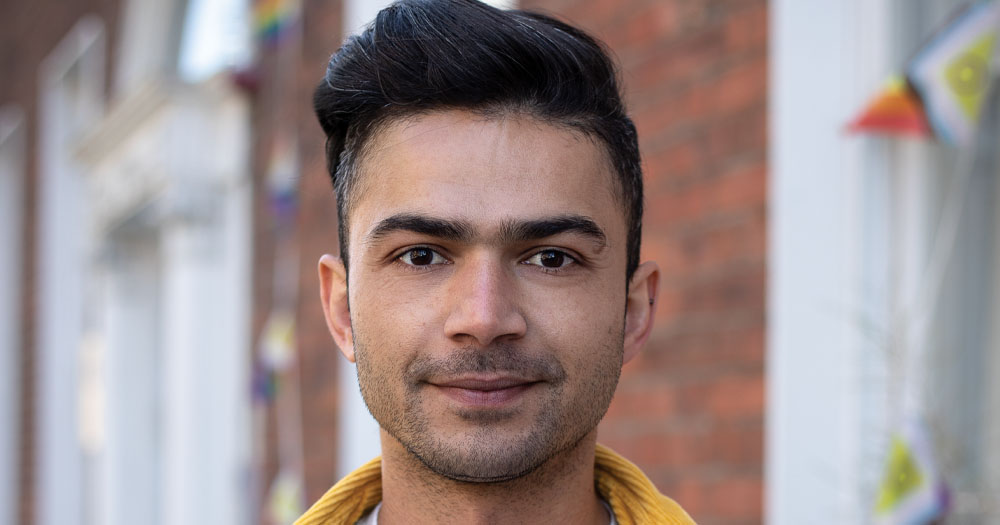

One person who is all too familiar with the impact of the far-right movement both here and in his home country of Brazil is Diego Caixeta. Diego has been living in Ireland for the past 13 years, and during that time, he worked for the Gay Men’s Health Service, before joining the MPOWER Programme at HIV Ireland.

Over the past few years, Diego has been following Brazil’s political situation intently while witnessing a similar wave of far-right rhetoric rise in Ireland.

“We had a far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro,” Diego explains. “He was in the same wave as Trump, and stayed in power for four years, causing destruction.”

Bolsonaro’s presidency was defined by his antienvironmental and pro-gun stance. During his time in office, he disseminated misinformation through the promotion of fake news. He rolled back protections for Brazil’s Indigenous peoples. Poverty and hunger increased, while social inequality reached its worst levels since 2012.

Bolsonaro’s anti-LGBTQ+ stance was clear even before he was elected, when he professed that he would be “incapable of loving a homosexual son,” and expressed concern over Brazil becoming a welcoming place for the LGBTQ+ community. Last year, Brazil was the country with the highest rate of murdered trans people for the 14th consecutive year.

Bolsonaro’s election, Diego feels, came as a result of a campaign of manipulation and exploitation, one that encouraged the public to blame minorities for wider problems. It’s a similar mechanism that mobilises the far right around the world.

“It’s always the same,” Diego says. “They take the opportunity of a crisis, and they use a very simple narrative to get people engaged with them. They are democratically elected, but when they are in power they start destabilising democracy, to try to be in power and cause all the destruction that they do.”

Bolsonaro ran for re-election in 2022, but was defeated by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a centre-left candidate. Despite this change in presidency, the right wing parties that sided with Bolsonaro make up half of Brazil’s congress. With this, Diego worries that Bolsonaro’s legacy will continue to jeopardise the lives of Black people, the LGBTQ+ community and Brazil’s Indigenous population.

“The far right have an umbrella of targets,” Diego explains.

Still, he is hopeful for Brazil’s future. “I think there is always hope,” he says. “You have to have hope. There are strong groups trying to push legislation to protect minorities. On the other hand, it’s tricky. Our Congress is very conservative and full of extremism, and we have a big rise in evangelism. It’s very easy to get their narrative across when they use religion as an excuse for what they’re doing.”

In Ireland, Diego has concerns over the escalation of far-right violence we’ve seen this year. “I think the far right hasn’t fully looked into Ireland with the same urgency they did in other countries, but they are around. We’ve seen all the protests against migrants, setting tents on fire, trying to block refugees from going to hotels. I hope that Ireland can start acting now, but you have to act in a very strong way.”

With a number of people becoming radicalised via social media and misinformation, Diego believes greater regulation could make a difference, if executed swiftly.

“Social media is so powerful, but it’s not so well regulated. I know Europe is trying to legislate it, but technology is way faster than legislation,” he says. “Social media platforms are allowing people to say whatever they want to say. I don’t think they understand that what is a crime offline is still a crime online.”

Ireland, Diego Caixeta believes, can look to Brazil to understand how quickly the far right can grow, and its ensuing consequences.

“Here in Ireland, we can predict things and hope the Government takes it seriously. Especially with the situation regarding healthcare and housing. No one can access these things at the moment, so it’s very easy to target minorities and blame them for everything, and that’s how xenophobia and racism rises, and that’s what the far right does.”

This story originally appeared in GCN’s Pride issue 378, as part of an ongoing feature on solidarity that was created in cooperation with the Rowan Trust and the Hope and Courage Collective. You can read this interview with Diego Caixeta and other activists in the full issue here.

Want to be featured in this special campaign? Share a message of solidarity using #StrongerTogether, tagging GCN or email [email protected].

© 2023 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

This article was published in the print edition Issue No. 378 (June 1, 2023). Click here to read it now.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.