Flikkers nightclub formed a crucial part of Dublin’s LGBTQ+ life during the 80s. The annual Halloween Balls became the stuff of legend. So much so, that the iconic imagery associated with the nightclub inspired artist, Brian Teeling, to create designs for the GCN merch series, PROTEST!

Former Flikkers DJ and historian, Tonie Walsh, explains why it was more than just dancing and flirting.

Dancing and Socialising as a Political Act

One of the earliest electronic music venues in Ireland, Flikkers opened to great fanfare on St Patrick’s Day 1979. Such was the clamour for LGBTQ+ social services – when a commercial scene barely existed – some hundred dejected punters remained outside unable to access the crammed building.

Flikkers (Dutch for ‘faggots’) was housed in a three-story warehouse, the Hirschfeld Centre, headquarters of the National Gay Federation (NGF) on Dublin’s Fownes St. The building was a second attempt at establishing a queer community space, following in the footsteps of the Irish Gay Rights Movement (IGRM).

View this post on Instagram

Named for the pioneering gay activist, Dr Magnus Hirschfeld, the centre housed a café, small library, a 55-seater 16mm cinema/lecture room, women’s group, youth group, offices for Tel-A-Friend (now know as Gay Switchboard), NGF and the International Gay Association’s information secretariat and, at its centre, the dance club that funded these social, cultural and political facilities.

At a time when statutory funding was unheard of, all of the building’s services were run by volunteers, with the exception of a paid manager. Both the name of the dance club and the building were designed to patch Irish LGBTQ+ people into a wider civil rights history on mainland Europe that stretched back to the early 20th century, reminding us that there was queer life and activism aplenty even before Stonewall.

At a time when LGBTQ+ women and men were routinely refused service in bars and clubs, Flikkers provided a safe space where Irish queers could unburden themselves of the homophobia and hostility that was as widespread as the country’s economic impoverishment.

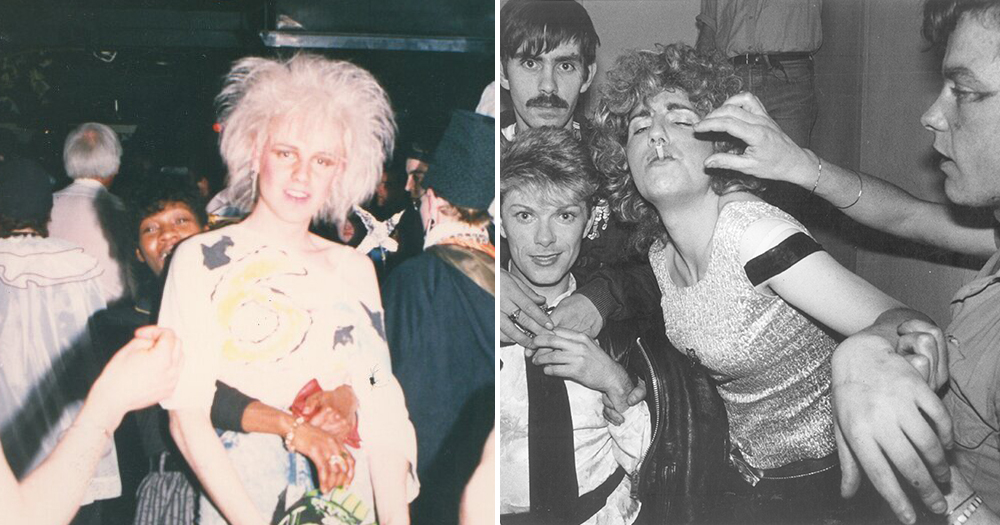

Photograph by Seán Gilmartin

Throughout the 1970’s and ’80s, Irish society was bereft of positive queer images and the sight of two women or two men dancing together – especially to a slow set – was both revelatory and subversive. Socialising and dancing together became an inherently political act.

There’s a moment in the documentary film, Notes On A Rave, when Limerick DJ, Paul Webb recalls: “Coming into somewhere like Flikkers, it was just a whole new world. It was brilliant. How do you explain it? It was like being reborn; when you are going out clubbing and you don’t want the same 20 clubs up on Leeson or Harcourt St all playing the same 20 songs, down here it was a whole new world.”

Webb could have been referring to the eclectic mix of punters as much as the playlist and sound system. With a capacity for some 400 people, spread over two floors, the dancefloor included twin sets of Bose horns flown from a low ceiling, offering crisp, surround sound stereo; two bass bins and one of the earliest sets of Technics 1200 turntables to grace a music venue in Ireland. Behind the DJ booth was a walk-in library of thousands of vinyl 12” singles, 45’s and albums that helped to define the “Flikkers Sound”.

Designed by Francis Scappaticci.

DJs were encouraged to rehearse their mixing skills and a premium was put on the ability to beat mix, at a time when this was unheard of in other entertainment venues. The club had subscriptions to limited edition DJ remixes in the USA, France and Netherlands that kept Flikkers months ahead of the mainstream. Flikkers was one of the earliest venues to play house music as it emerged from the embers of disco.

As it was a private members club, Flikkers operated to different rules. Bank holidays often meant staying open to 6am or 7am, with breakfast of coffee and croissants thrown in for good measure. From the mid-’80s onwards, a roster of big-ticket acts, both Irish and foreign, performed at the club; home-grown talents like Lord John White and Some Kind of Wonderful were complimented by monster dance stars Odyssey (of ‘Going Back to My Roots’ and ‘Inside Out’ fame) and Viola Wills (‘If You Could Read My Mind’).

The highlight of the social calendar was undoubtedly the Flikkers Halloween Ball, inaugurated in 1982. Big prize money was offered for the best costumes (that ranged from straightforward drag to fantasy or weird art school mash-up). At a certain point, just after midnight, contestants got to sashay in their finery on a runway, before the pumped-up crowd got back into the business of dancing into the early hours.

View this post on Instagram

The last Ball was held on 31 October ’87, four days before the building was catastrophically damaged by fire.

Flikkers occupies a much cherished and pivotal role in the social, cultural and political life of Irish LGBTQ+ people. It allowed a generation of queer men and women to find each other and build a community, the results of which are all around us today.

Brian Teeling’s PROTEST! collection features the original 1979 disco logo on badges.

The tee-shirts feature a mid-1980’s redesign of the logo by Tipperary man, Michael Carmody, who would die tragically young.

The reverse of the Flikkers tee-shirt features a ticket for the, itself a fundraiser for GCN held at Dublin’s Irish Film Institute. Designed by Tonie Walsh, it features his then boyfriend, Tim, masquerading as a G&T with a slice of lemon as a headdress.

Merch from the PROTEST! collection can be purchased here.

View this post on Instagram

© 2021 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.

comments. Please sign in to comment.