The contribution of women in the Easter Rising is a sadly underreported one. The historical narrative familiar to most details the struggle of a small but doomed band of brave men battling the insurmountable might of the British empire. But there were women who took part in the Rising, many women, and among them were more than a few women who loved women. That their contributions have been not just overlooked, but in some cases literally airbrushed out of the 1916 story, is a tragic disservice to Ireland’s heroic women.

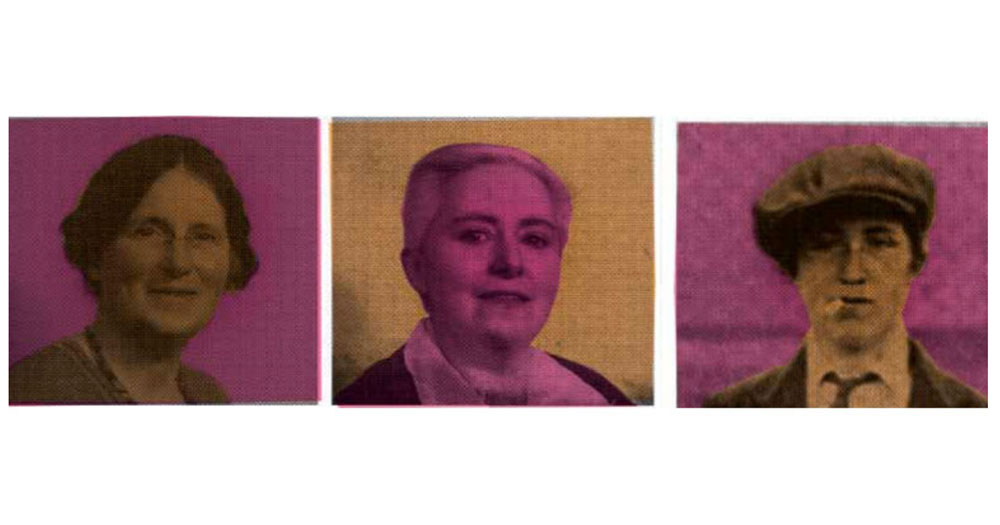

Although ‘lesbian’ isn’t necessarily how they would have identified themselves – it is important to acknowledge and to approach any discussion in the context of the time – the fact is that some of the women of the Easter Rising were in same-sex relationships, and unapologetically so. Kathleen Lynn was one such woman. Born in Mayo in 1874, Lynn was a doctor (her portrait, the only female face among a sea of masculine oil paintings, still hangs in the Royal College of Surgeons), a suffragette, an active member of the labour movement, and was chief medical officer during the Easter Rising. Her partner, Madeleine French-Mullen, born in Malta, was the daughter of a British Naval Officer with Irish connections and was an ardent suffragist.

The pair met during the 1913 Lock Out, where Lynn was giving first aid lectures and administering free medical treatment to the striking workers and their families, and remained together until Madeleine’s death in 1944. Both women joined the Irish Citizen Army together providing medical support and on Easter Monday, Lynn found herself based at the unenviable position of City Hall (which backs onto Dublin Castle, HQ of the British Army), while ffrench-Mullen was at College Green.

When Lynn arrived at City Hall with medical supplies she discovered that Sean Connolly, an actor in charge of that garrison, had been mortally wounded by an errant gunshot. When it became clear that he wouldn’t survive, she found herself the ranking officer of the group of 16 men and nine women stationed there and so, assumed command of the outpost. Its proximity to the headquarters of the British Army meant that it came under heavy fire and after a single day the rebels were arrested. The legend goes that when the commanding British officer demanded to see the ranking rebel officer for his surrender, he was aghast to learn that it was a woman.

Eventually, the shock faded enough for him and his troops to escort Lynn and co. to Ship Street barracks, before transferring them to Kilmainham. Sharing a squalid cell with Lynn, French-Mullen wrote in her diary at the time that “as long as we are left together, prison was somewhat bearable”. Later Lynn was transferred to Mountjoy, which she noted was a cleaner jail with better conditions for prisoners, but wrote in her diary “but I would give £10,000 to be back in Kilmainham with Madeleine.”

In 1919 Lynn and ffrench-Mullen, together with many of their female comrades, founded St Ultan’s hospital, the first all-female staffed hospital for infants in the country. The couple lived together in Rathmines until ffrench-Mullen’s death in 1944. Despite what appears to be overwhelming evidence to suggest that Lynn and ffrench-Mullen were in a longstanding same-sex relationship, this was until recently a matter of contention among some historians. The lesbians of the Easter Rising were in essence hiding in plain sight. Since they didn’t identify as lesbians (such popular determinations were still years away), and since they were living unconventional lives away from the kitchen sink and the trappings of domesticity anyway, scrutiny about their sexuality was non-existent.

“They were able to have those relationships in plain sight because of course they were two women living together, two unmarried or ‘spinster’ women as we could call it, and that was not unusual in that society,” says Dr Mary McAuliffe, lecturer in Irish Women’s History at UCD. “So they didn’t have to come out, they didn’t have to do that identification because it was quite normal for two women who had not married to live together as companions, as friends.

“The fact that we know they had more than that in their lives comes through in diaries and memoirs and private correspondence about them – it isn’t in the public record, but their hidden history is part of the hidden history of women anyway, and if women were hidden, lesbian women were twice as hidden. “At that time sexuality for women was constructed as reproductive, marital and passive – you didn’t make choices around sexuality if you were a woman, straight or gay. So, the histories of sexuality for all women are pretty hidden. But if you’re anything other than straight, it’s really difficult to find those histories.”

Another notable and often overlooked couple were Elizabeth O’Farrell and Julia Grenan. Friends since childhood, both women were nurses stationed at the GPO. It was O’Farrell who brought out the white flag of surrender and whose feet were literally airbrushed out of a photograph so it showed Padraig Pearse surrendering alone. The women lived together their whole lives and were buried in the same plot in Glasnevin cemetery. The inscription mentions Elizabeth O’Farrell then adds “and her faithful comrade and lifelong friend, Sheila Grenan”. The subtle language of the hidden homosexual.

“That’s the type of language that was used for people who were committed to each other, both personally and politically – they said ‘lifelong companion’, ‘lifelong friend’, ‘my friend’ – they used terms like that because they don’t have other language in a way we have today,” says McAuliffe.

Despite being imprisoned along with Kathleen Lynn, rather early on Easter week, Helena Molony, an Abbey actress, was another unheralded but key member of the Easter Rising. She was unquenchably radical, even trying to dig her way out of Kilmainham gaol with a spoon after her capture.

Kathleen Lynn later attributed her politicism in part to the influence of Molony, who stayed with her and French-Mullen in the basement flat of their Rathmines home. Born in 1883 and orphaned early in her life, Molony was a radical committed to the intertwined causes of feminism, the labour movement and national sovereignty. In 1908 she established Bean na hÉireann, a monthly magazine advocating ‘militancy, separatism and feminism’ – the only magazine promoting physically aggressive republicanism.

In 1911 she earned the distinction of being the first Irish political prisoner of her generation after vandalising a portrait of George V during his visit to Ireland. She was bailed out, but was overjoyed when she was rearrested for calling the monarch a scoundrel. “That was marvellous; I felt myself in the same company as Wolfe Tone,” she later said of her brief detainment. So enthusiastically did she believe in the cause of the Easter Rising, she spent the weeks leading up to the event sleeping on a pile of coats at workers’ co-operative store adjoining Liberty Hall, with a revolver under her pillow.

She was involved in a dramatic raid on Dublin Castle which resulted in the murder of an unarmed police officer, before being captured in City Hall and imprisoned in Ship Street barracks. She was then moved to Kilmainham Gaol where she was traumatised by the executions of the Rising’s leaders. After a failed but valiant attempt to dig her way out with a spoon, she became one of only five women to be transferred to a decrepit jail in Aylesbury, England, together with 2,500 of the conflict’s male combatants.

After her release, Molony continued to campaign for equality for women (and against the rescinding of the principle of equal citizenship enshrined in the Proclamation) against a pro-Treaty Labour Party and a male-dominated trade union. Despite opposition to her firebrand ways, she was elected president of the Irish Trade Union in 1937, becoming only the second woman to hold the office. Despite a number of rumoured affairs with men (including Sean Connolly), she lived with psychiatrist Evelyn O’Brien, from the 1940s until her death in 1967.

“I’m pretty sure that Helena was bisexual,” says Marie Mulholland, author of The Politics and Relationships of Kathleen Lynn. “Helena had a number of affairs with men but certainly the last 20 years of her life she spent with O’Brien. When O’Brien died, her family ensured that all over her personal papers were destroyed, which is always an indication that something is being hidden. “Another possible addition to the queer pantheon of 1916 heroes is Margaret Skinnider, a slacks-wearing sharpshooter who was the only woman to be injured during the Easter Rising.

Born in Scotland in 1892, the daughter of Irish parents, Skinnider became an active participant in the women’s suffrage movement and the fight for Irish independence as a young woman. After getting involved with Constance Markievicz, Skinnider began smuggling bomb-making equipment and detonators into Dublin (hidden under her hat) ahead of the Easter Rising. She joined the Irish Citizen Army as a dispatch rider and was a scout and sniper for the St Stephen’s Green garrison. She was mentioned three times for bravery in dispatches sent to the GPO, before being shot three times and hospitalised. “In pictures of Margaret she is always dressed in boys clothes,” says Mulholland. “She insisted on being dressed as a boy for the Rising, because since she was a crack shot, she had to move very quickly around the city as a sniper. She wanted to be able to move efficiently, so she pooh-poohed the idea of being in a skirt.”

Skinnider didn’t brook any discussion about her right and capability to take place in such a violent uprising, telling a sexist commander that “we had the same right to risk our lives as the men; that in the constitution of the Irish Republic, women were on an equality with men. For the first time in history, indeed, a constitution had been written that incorporated the principle of equal suffrage.”

After her injuries, Skinnider was deemed too ill for imprisonment and managed to evade capture on her release from hospital. She fled to Glasgow before making her way to the US, where she fundraised for the republican cause. She was active during the War of Independence and Civil War (she opposed the Treaty) and in 1922 became paymaster General for the IRA. She was eventually imprisoned and held in the North Dublin Union where she became Director of Training for the prisoners. After her release from prison Skinnider worked as a teacher in the Sisters of Charity primary school in Kings Inn Street, Dublin where she remained until her retirement in 1961. She became President of the INTO in 1956, where she continued to campaign for the rights of women. She never married and died in 1971.

Finally, after 100 years, the contributions of these women and the stories of their lives – and loves – are beginning to surface, helping us to expand understanding of the events of 1916. “It’s changing and we see that they did contribute, that they were vital to the fight for Irish freedom, and that their personal lives and their personal histories – whether they were straight or gay or whatever – are absolutely central to our understanding of social, economic, political histories of the time,” says McAuliffe.

For some people though, there will never be enough proof of the nature of women like Kathleen Lynn, Elizabeth O’Farrell and Helena Molony’s sexual orientations. “There is resistance,” says McAuliffe. “People are still homophobic; backwards sometimes. People say: ‘there is no proof’ and it is very difficult to find proof. How much proof do you actually want?”

This article originally appeared in GCN Issue 316, April 2016, read the issue here.

© 2016 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

This article was published in the print edition Issue No. 316 (April 1, 2016). Click here to read it now.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.

comments. Please sign in to comment.