The story of LGBTQ visibility in Ireland is not one of oppression to liberation. Rather, it is a continuous tug-of-war, between the Irish LGBTQ community battling for column inches and screen representation and media institutions looking to co-opt their identities and sensationalise them. This argument forms one of the central points of my recent book, LGBTQ Visibility, Media and Sexuality in Ireland.

Since the establishment of varying Irish gay civil rights movements in the 1970’s, media visibility has been a central political goal of many of the groups that have formed throughout the island. Often, this visibility was strategised as a way of reaching out to LGBTQ individuals within a climate of criminality, as a way of counteracting the government apathy to the AIDS crisis, and even as means of simply showing that a welcoming community existed for people, amidst a society of brutal homophobia and one that reinforced a crippling silence around queer lives.

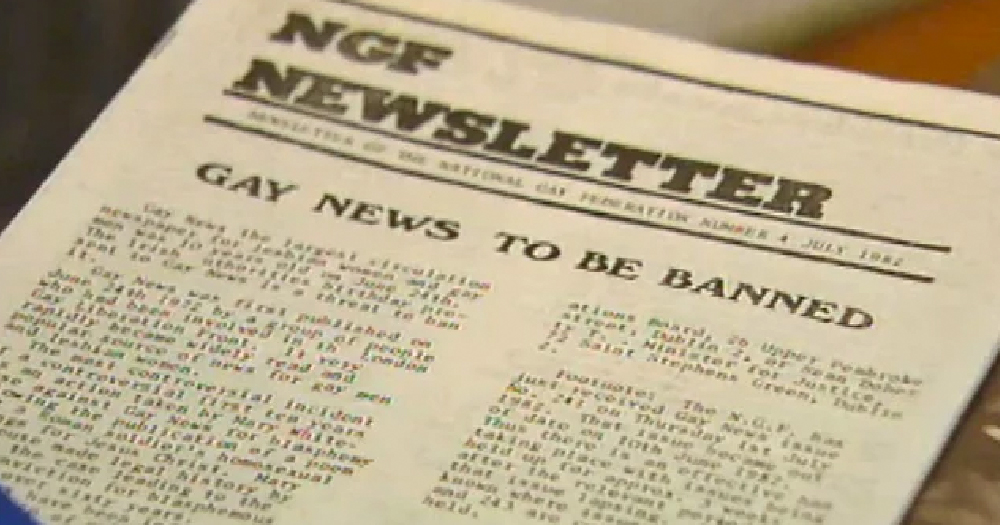

With the formation of gay liberation, the media quickly became a battleground of representation, where new meanings and conceptualizations of queer identities began to emerge, as groups like the Irish Gay Rights Movements, the National Gay Federation and the Cork Gay Collective canvassed and lobbied media for more representation. Key players of the early movements, such as David Norris, Arthur Leahy, Joni Crone and Edmund Lynch played a significant role in securing prime-time television slots and column inches for a burgeoning community of liberationists and activists.

The IGRM’s agitation, or demands, to obtain representation on RTÉ, coupled with Edmund Lynch’s insider role within the organisation as a sound engineer, resulted in the first appearance of an LGBTQ individual on Irish television in 1975, when David Norris appeared on the Summer magazine programme Last House. This was to be followed by a Tuesday Report documentary in 1977 that focused on homosexuality in Ireland. 1980 saw gay liberation in Cork secure visibility on current affairs show Week In, where Cork couple Arthur Leahy and Laurie Steele came out and discussed their relationship on national screens. In 1980, Joni Crone also became one of the first lesbians to come out publicly in Ireland when she appeared on The Late Late Show.

Many of these appearances were harnessed by early gay liberationists to disentangle gay and lesbian sexualities from anachronistic, generic stereotypes, to make available to isolated LGBTQ people an awareness of shared existences and desires and to simply provide an index that gay people did exist.

While the fight for decriminalisation of homosexuality, along with the development and sustaining of political and social hubs such as the Hirschfeld Centre formed a large part of the activism of Irish LGBTQ civil rights, media activism proved central to shifting public opinion and holding institutions of power accountable.

When gay pioneer (and GCN co-founder) Tonie Walsh was president of the NGF in the 1980’s, he noted how he fostered media activism into the politics of the organisation: “The tabloids, they were purveyors of really reductive stereotyping, so they were the ones that needed the most work, the most challenging. So I made a point of going after them and cultivating and deepening personal relationships with their chief reporters and feature writers…cultivating really good relationships that I could actually give them a story and guarantee it would actually appear the following weekend.”

This media activism became even more crucial during the evolving AIDS-epidemic in Ireland. Government inertia, coupled with sensationalist framings of AIDS in mainstream media produced and configured gay men into media frames that vilified and subjugated them to narratives of shame and stigma. Both of these factors led to the incubation of AIDS media, where the LGBTQ community generated visibility on their own terms, as their public health needs were forgotten amidst an innate and damaging silence.

The gay press, in particular OUT magazine, began to communicate crucial information on AIDS, producing community health guidelines, even including instructions on how to use a condom. Independent documentaries were also produced to provide Irish people living with AIDS a voice, such as Alan Gilsenan’s Stories from the Silence (1990) and Bill Hughes’ Fintan (1994).

Inasmuch as visibility can incite change, ensure more representation and hold institutions of power to account, the tug-of-war nature of public visibility similarly co-opts and regulates LGBTQ visibility in varying ways. The Late Late Show for example often attempted to frame LGBTQ sexualities through televisual sensationalism, framing sexual identity as a source of debate, all with the aim of producing high television ratings.

Such was the case with the appearance of lesbian ex-nuns Nancy Manahan and Rosemary Curb in 1985 and a debate about decriminalisation in 1989. While the pioneering chat show is often praised for its role in opening up Ireland to the realities of sexual identity, its production culture tended to use LGBTQ identity for the economic ends of ensuing good ratings, a facet of the story of The Late Late that is often ignored.

Visibility can obscure as much as it reveals. Such is the case with LGBTQ visibility in Ireland, where media institutions, particularly up until the 2000s, tended to consider solely gay male visibility, leaving lesbians and the broader LGBTQ community on the fringes, offering minimal entry into the fold.

While media visibility and media activism are an important facet to the story of Irish LGBTQ civil rights and LGBTQ representation, our consideration of it must avoid condensing it into a narrative of progress. Rather, we can appraise its merits all the while exposing and contending with visibility’s tug-of-war.

Páraic’s book, ‘LGBTQ Visibility, Media and Sexuality in Ireland’, will be launched virtually on Zoom on March 5 at 7pm, with a panel including Tonie Walsh, Rita Wild, Prof. Maria Pramaggiore and Dr. Patrick McDonagh. You can register to attend here.

It is also currently available to order here.

© 2021 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.