“Generally the neighbours don’t bother with me. It’s quite isolated and I still have my down days.”

“If I step outside my front door, I’m making a political statement,” says Christine Beynon. The 74 year-old has lived in the tiny village of Mullacuttra in the townland of Claregalway since 1979, but it’s only for the last seven years that she’s been living openly in her gender identity. “The first person that knew about it was the postmistress because mail began to come addressed to my female name,’ she says. “She was fine with it, and I asked her if everyone knew about it now, and she said yes. So people knew without me telling them. I didn’t go knocking on people’s doors, saying ‘Hi, I’m Christine’.”

Christine isn’t a native of Connaught, as her gentle cockney accent gives away. Born and bred in the East End of London, she spent her childhood and most of her adult years pushing her true identity away.

“I noticed there was something different about myself when I was ten or eleven years old,” she says. “My mum used to catch me putting on her make-up and she’d give me a clout. When I was 16 I saved up my pocket money and bought a hat that looked like a wig. I had it in a box under the bed where I kept a few bits. I got a black sequined ballroom dress from an aunt. I wore it once and everybody laughed at me, so I disappeared into the closet. I knew there was something wrong, that I shouldn’t be doing it.”

Married Life

After leaving school she worked in her uncle’s chairmaking factory, before leaving to go into warehousing, and that’s where aged 20 she met Celia, the woman who would become her wife.

“She was married at the time and had a baby,” says Christine. “She came from Claregalway and had moved to London when she was 17. She left her husband and we lived together from 1965 until 1970, until she got a divorce and we got married.”

The couple, along with Christine’s son and a daughter of their own, relocated to Ireland nine years later.

For the duration of their long marriage, Celia, or Chris as she was known to family and friends, didn’t know about her husband’s gender identity.

“I thought that getting married and being in a straight relationship might make it go away, but it didn’t,” says Christine. “When my wife went shopping or whatever, I took the opportunity to wear her clothes. It was very mild, not fully dressed up or anything. I was always looking around me, wishing I was a woman.

“After a while, I had a box of clothes in the attic, and she’d go and visit a neighbour and I’d get them down for ten or 15 minutes, hoping she wouldn’t come back and catch me. I’m sure in a way I wanted to be caught, while at the same time not wanting to be caught.

“It made me really secretive within my marriage when I didn’t want to be secretive. I had to watch what I said in case I said something inappropriate that might give me away. I used to go shopping with my wife, but I couldn’t allow myself show interest in the clothes.

“In later life, I think she knew, but we never spoke about it. Out of sight, out of mind.”

Chris passed away from breast cancer in 1998, and in the aftermath, Christine was both liberated and crushed.

“For the last two weeks of her life, when my wife was in the hospice, I was at home dressed fully as a woman. I’d given up my job to look after her, and I’d done my best by her, but this really affected me for years, that I had been deceiving her. I felt very guilty and I went through a period of bad depression.

“After Chris died, the neighbours said they’d be supportive, but they weren’t really. They sort of melted away. That’s the way people are. They say, ‘I’ll give you a ring next week,’ but it never happens. So I became very isolated. There was no help, nowhere to go, nothing to do. Nobody knew about me.

“The house went to rack and ruin. It took me eight years before I could come out and be true to myself, to get my life and get over it. I had to do it, otherwise I wouldn’t have lasted. I would have checked out.”

Same Journey, Same Time

After a while, Christine began to find out more about trans identity on the Internet, which she says opened up a whole new world to her. “I found a dressing service in the East End of London, not far from where I grew up, so I went to see them,” she says. “That’s where I started dressing fully. I met Helen, another trans woman in the same situation as myself, who had been through a marriage and had children, and we became good friends. The two of us were on the same journey, at the same time.”

As many trans people who haven’t found the courage to access the medical system often do, Christine began to self-medicate with hormones she bought online. She ended up in the Galway Regional Hospital coronary unit after an overdose, where she said nothing to doctors about the hormones she’d been taking.

“After I got home I decided not to take them anymore,” she says. “It was too dangerous, so I decided to go the legal route. I went to a doctor in London, and I had to see a psychiatrist and a psychotherapist before any surgery took place. A lot of people complain about how long it takes, but I think you need that part of the journey. Later on in life, some people regret transitioning, so I think it’s important to go through the stages, to make sure it’s something you won’t regret. It took three years. I had to live for one year full-time as a woman, here in Ireland.”

Living Full-time as Christine

At the beginning of living full-time as Christine in Mullacuttra, she only went out at night, driving around country lanes in her car. When she began to go out in daylight, people didn’t fully acknowledge her, and that’s the way it’s stayed since then. “Generally the neighbours don’t bother with me,” she says. “It’s quite isolated and I still have my down days.”

However, one unlikely member of the community was surprisingly open and friendly. “The one that surprised me was the parish priest. He’d seen me in Claregalway as Christine a few times, and I’d waved at him, but he didn’t recognise me. Then one day he turned up at my door. I said, ‘Come in Father,’ and he said, ‘I’m glad I’ve caught you at home’. We had a chat for about ten minutes. I see him now and then and we say hello. He accepts me as Christine; he calls me Christine.”

Although Christine has been accepted by the local priest, the daughter she had with Chris has found it difficult. “I told her about myself in 2006, during the bad times, and from that day to this, she’s never come to see me, even though she only lives 20 miles away,” says Christine. “When I was going for my surgery, I called her to let her know. She said, ‘I can’t even say your name’.

“It’s her life, and she’s old enough to make her own decisions. I made my decision. I had to live my life for me.”

On the other hand, Christine’s stepson, who now lives in Australia, is fully onboard. “He came to London at Christmas in 2014 and met me as Christine for the first time in Victoria Station. I was staying in Brighton and we spent Christmas together there. He’s coming over again this year.”

Over the years, Brighton, and a particular hotel there called Legends has become Christine’s escape from the isolation of country life.

“It’s a gay hotel, owned by a gay person and all the staff are gay,” she says. “It’s become a second home to me, a place to go where I’m fully accepted. “When I go there, people ask me if I would move there, but I say ‘no’. Why should I change? Mullacuttra is my home. I’ve lived here for more than 40 years.”

Selfie Exploration

The residents of Christine’s village might largely ignore her, but that doesn’t mean she goes unscathed elsewhere in the region. “I get called names, but I ignore it,” she says. “The other day I went for a walk with a trans friend on the promenade at Salthill, and we got a few yards before a couple said, ‘Are those two women, men?’ It made us laugh, it’s a funny comment really.

You get looked at and things like that, but the more you get out and get seen, the more confident you become. The people who do call out are usually young guys, but they only call out when they’re in a car.”

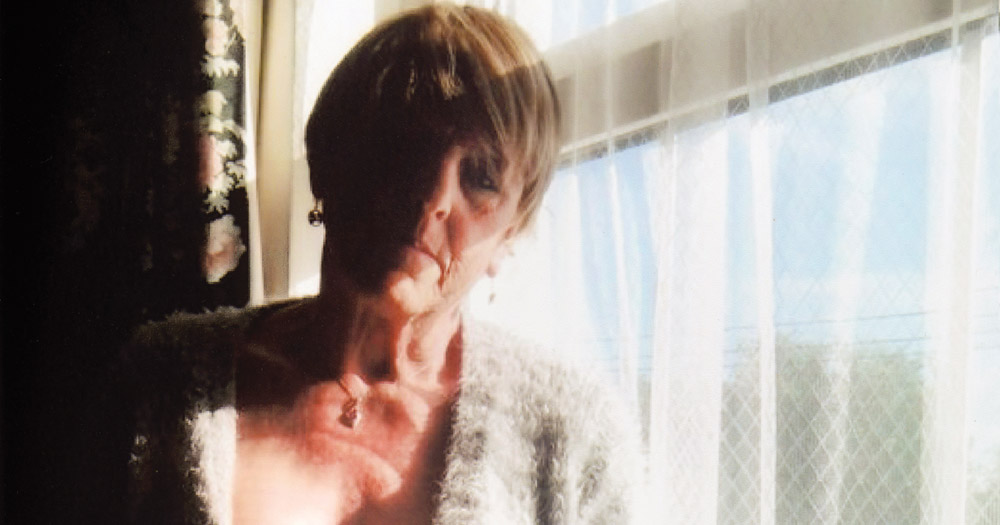

Throughout the years leading up to her transition and beyond, Christine has visually documented herself by taking selfies. This vast collection of photographs attracted the artist Amanda Dunsmore, who first met Christine in 2012 when was working on a commission for Galway County Council based around the older generation of the LGBT+ community. With Christine’s photographs as a centrepiece, Dunsmore has created an exhibition called Becoming Christine, which opens at the Royal Hibernian Academy this week.

“There was nobody to take photos off me, so I had to take them myself,” says Christine. “Amanda had been looking at the selfies on Facebook and she came to me and said she wanted to do a visual show. They’re not selfies as you might think of them, though.

“I’ve never said that I would pass, so I got that out of my head, the idea of trying to pass. I’m just being me. I’m trying to be presentable. People often say to me that I’m always well dressed, and I say, ‘I have to be. I have an appearance to keep up’.

“All I want is to be accepted for who I am, but when I step outside that front door, I can’t hide, not from anyone and not from myself. I walk out the door and I’m saying ‘this is me’.”

Becoming Christine’ runs from September 7 to October 21 at the RHA Brown & O’hUiginn Galleries in Dublin, find out more here.

© 2018 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.