The Irish Gay Rights Movement marks its 50th anniversary this year. It may have been short-lived, but the Sexual Liberation Movement (SLM), established in late 1973 at Dublin’s Trinity College, seeded many critical, foundational connections in Ireland’s nascent LGBTQ+ civil rights movement.

The radical, ad-hoc Gays Against Repression (GAR) immediately comes to mind as does the more mainstream, reformist organisation, the Irish Gay Rights Movement (IGRM).

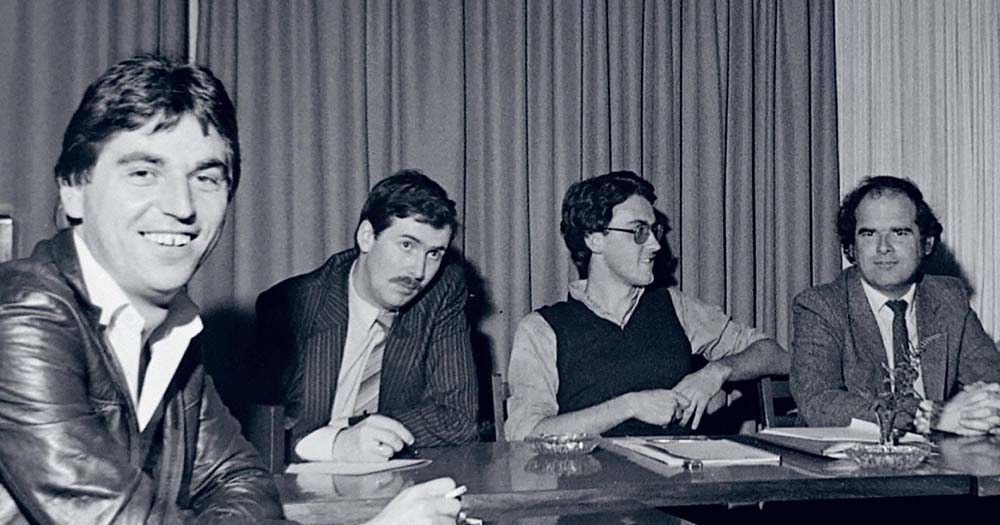

Just four months after SLM organised an enormously successful symposium on homosexuality, IGRM was established in June 1974 by a group of people, some of whom had met either at SLM or its homosocial space, The Good Karma, on Strand Street. Among the group were David Norris, Seán Connolly, Clem Clancy, Edmund Lynch, Kenneth Jackson and Martin Barnes.

A public meeting was called on Sunday, July 7, at Dublin’s South County Hotel, formally ushering in IGRM with the clarion call: Who Are Homosexuals?

Many of the 30 people in attendance would go on to play pivotal political and social roles in the new gay civil rights organisation.

An office was quickly acquired at 23 Lower Leeson Street, and when discos at The Good Karma came to an end, IGRM began hosting cheese and wine fundraising events from its downtown HQ.

“All of us involved at the time, some more publicly than others, would have been in our mid-20s and upwards,” remembers Clem Clancy, who assumed the role of treasurer and financial controller. “We had full-time jobs, were confident and secure, although some people worked behind the scenes for fear of being exposed publicly and risk losing their jobs.”

The organisation grew rapidly in its first year, cultivating support from Ireland’s liberals, among them Dr Noel Browne, former Minister for Health, and Kadar Asmal of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties who helped IGRM prepare an early draft of a Sexual Offences Bill.

A constitution was adopted in September 1975. Among its objectives were the achievement of equality under the law, the acquisition of premises for social activities and the provision of befriending services.

In tandem with the Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association (NIGRA), switchboard services Cara-Friend and Tel-A-Friend (TAF) were set up on respective sides of the border. TAF, now called The Switchboard, remains the oldest, continuous LGBTQ+ organisation on the island of Ireland.

Joining the executive at this point were Terri Blanche, Jimmy Malone, Noel Clarke, Kenneth Watters and Seamus O’Riain, all geared up for the next phase in IGRM’s history.

A circular from Oct 1975 announced the commencement of the Phoenix Club Disco every Friday and Saturday in the basement of 46 Parnell Square East. An exclusively women’s night, The Lavender Room, operated once a month, helmed by among others, Phil Carson, Terri Blanche and Joni Crone.

“Initially we had the ground floor and basement of No. 46, but within six months we took a two-year lease on the entire building, in effect establishing Ireland’s first gay community centre,” recalls Clancy.

The Cheese ’n’ Wine events continued on alternate Sunday afternoons. The expansive four-storey-over-basement Georgian building at Parnell Square allowed for the establishment of a library, and various sub-committees met in the upstairs offices, focussing on legal, educational, media, social and religious affairs.

Noel Walsh recalls setting up a theatre group, The Phoenix Players: “It was amateur night at the Ritz!”

“How it came about was we did a pantomime. I can’t remember the actual date but I’ll say it was Christmas of ’76. Terry Shadwell, who later edited In Touch newsletter, was also involved. We turned the basement disco into an auditorium and the toilets doubled up as dressing rooms.

“The pantomime script was fairly loose. It was hilariously funny because none of us had done anything like this before, but we wanted to have some fun and do more social stuff. Someone even went to the trouble of printing ‘Phoenix Players’ t-shirts, which may have been overly ambitious as we ever only did that one pantomime.

“There was talk of putting on Many Young Men of Twenty, the John B Keane play, but nothing came of it.”

The 1970’s was an exciting if troublesome decade in Ireland. Civil rights agitation was a daily occurrence in the North, along with a corresponding spill-over of violence. The second wave of feminism was in full swing, as was public service broadcasting.

Ireland joined the European Economic Community (progenitor to the EU), membership opening up the possibility of new economic, cultural and social links at a time when the country was wrestling with its religious and social conservatism and forever one step away from economic bankruptcy.

This was the decade when secondary school education became free, allowing a generation to dream and hope for better times. It was a decade when conversations around political, ethnic and gender identity loomed large and Irish Gay Rights Movement was very much part of that wider public discourse.

By late ’75, monthly coffee afternoons at random Leeside locations were sufficient enough to encourage the establishment of Cork IGRM. According to Patrick McDonagh in his terrific book, Gay and Lesbian Activism in the Republic of Ireland, 1973-1993, one of the biggest challenges the local group faced was finding suitable premises from which to organise.

It would be 18 months before Cork IGRM acquired such a space. One of its founders, Cathal Kerrigan, has a fond memory of the sense of community building that grew out of rehabilitating a run-down space at 4 MacCurtain Street and giving it a new sense of purpose: “We set up a little coffee bar and that’s how it began.”

Rural outreach programmes involved members of Dublin and/or Cork visiting various locations in Limerick, Waterford, the Midlands and Border counties with a view to putting isolated people in touch with each other and potentially seeding more formal structures locally.

As the organisation grew in strength, so too did its visibility. Irish Gay Rights Movement chairman, David Norris, became the first openly gay person to appear on Irish television in July 1975. RTÉ would return to Parnell Square in 1977 for an even bigger programme, Last House, that also featured interviews with other members of the organisation, including Jimmy Malone, Seán Connolly and Phil Carson.

By this stage, the organisation had championed two shows by Gay Sweatshop at Dublin’s Project Arts Centre. The English agit-prop theatre group’s appearance generated huge media interest and controversy, leading to Dublin City Council’s withdrawal of funding from Project.

Other fissures erupted, driven by ego clashes and ideological differences within the organisation.

After an administrative upheaval in 1977, David Norris, Bernard Keogh, Edmund Lynch, Tom McClean and Brian Murray left to pursue the establishment of the Campaign for Homosexual Law Reform. Within two years, they were joined by other former IGRM members Tony O’Shea and John Cronin, both resident DJs at the Phoenix Club during its halcyon days. This ever-widening group set about establishing a new organisation, the National Gay Federation (now known as NXF) and a new community space, the Hirschfeld Centre, in what was then a decrepit, run-down part of the city now known as Temple Bar.

No. 46 Parnell Square had been shuttered for over a year when the Hirschfeld Centre opened on St Patrick’s Day 1979, ushering in a new chapter in Dublin and Ireland’s LGBTQ+ history. However, within a year, IGRM was in a position to open a premises just off Bachelor’s Walk.

The location of the new Phoenix Centre on North Lotts presented all sorts of threat and danger, as much then as it does today. Eamon Redmond remembers his first visit to the centre in 1980. “I knew about the Hirschfeld Centre and often walked up and down the street but couldn’t find the courage to go in. I would have been 18 and a little bit awkward as I’m on the autism scale. So my first visit to the Phoenix Centre was with a guy whose name I’ve forgotten. One of the first people I met was Trevor Noble. You’d often see him working in the building.

“Most disco nights, Clem and Seán would be on the cash desk. Seán would have his back to the door, bracing for the regular kicking it got [from homophobic assaults]. For passers-by, there was no escaping the knowledge of what went on in the building as the brass plaque clearly spelled out the name: Irish Gay Rights Movement.

When leaving the premises, you’d always take a peek beforehand through the little spy hole to make sure the coast was clear. Once, a group attacked the door with hammers and axes. I have a photo of me standing next to the damaged door.”

Relations between the founding figures in IGRM and NGF remained frosty throughout the early years of the new decade, occasionally become hostile and petty. And quite public. Each organisation produced its own newsletter called In Touch, until NGF dropped the ridiculous conceit in 1981.

By this time, Trevor Noble was responsible for photos at In Touch (IGRM), even getting to redesign the newsletter’s masthead. “I always had a talent for or affinity with graphic design and had friends who were professional photographers.”

Noble’s relationship with IGRM stretched back to Parnell Square days, when he would often drive from his home in Ballinasloe to attend the weekend disco or meet fellow members of the “Lonely Gays Society,” one of the centre’s support groups.

Noble would also try his hand at some illustrations and cartoons, some of them quite risqué for the time and even more so today. He gave In Touch a complete overhaul for what would be its final outing in autumn, 1982. The 20-page, glossy-covered A5 edition overseen by IGRM general secretary, John F Ryan, included a feature on the Dublin Castle sex scandal, a critique of Roman Catholic thinking on homosexuality, two pages of personal ads and a short shorty/memoir by Joseph Ambrose.

By 1984, IGRM was no more, its social focus overtaken by the Hirschfeld Centre and a burgeoning commercial social scene, while its original political imperative was advanced by NGF, the Dublin Lesbian and Gay Men’s Collective, and smaller groups in Galway and Cork.

As it marks its 50th anniversary this summer, IGRM and the people who enabled it deserve our admiration and respect for establishing Ireland’s first LGBTQ+ community centre, for challenging the absence of positive lesbian/gay role models on Irish radio and television, laying the ground work for decriminalisation and equality legislation and ultimately establishing a legitimacy to our right to exist in Irish society.

Some of those founding members of the Irish Gay Rights Movement are sadly no longer with us, but many of the remaining others celebrated together at the special 50th anniversary event held on July 3 in the Morrison Hotel, Dublin 1.

The Irish Queer Archive at the National Library of Ireland holds a significant collection of IGRM organisational and financial records along with a full collection of its newsletters (1974-1982). Cork LGBT Archive also has a small collection associated with the Cork branch.

This story originally appeared in GCN’s June 2024 issue 384. Read the full issue here.

© 2024 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

This article was published in the print edition Issue No. 384 (June 1, 2024). Click here to read it now.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.