The pink triangle is one of the most notable queer symbols. Once a badge of shame sewn onto prison uniforms in Nazi concentration camps, it marked homosexual men as targets for persecution, violence and death. Today, it stands as both a memorial to a largely forgotten group of victims and a warning that the forces which enabled such atrocities have not vanished.

Under the Nazi regime, male homosexuality was criminalised. Tens of thousands of men were arrested, imprisoned or deported to concentration camps. Survivors’ accounts reveal that those forced to wear the pink triangle were vulnerable inmates, subjected not only to the brutality of guards but also to abuse from fellow prisoners. A study by Professor Rüdiger Lautmann found that around 60% of gay men in concentration camps died.

Lesbian relationships were generally not illegal across most of the Reich, with the exception of Austria, where they were criminalised. Elsewhere, lesbians were often arrested or sent to camps under the vague classification of “asocial”, a category used to punish women who failed to conform to Nazi ideals of heterosexuality, domesticity and motherhood. This same label was generally applied to transgender people, whose identities were viewed as deviant and a threat to the rigid gender order the Nazis sought to enforce.

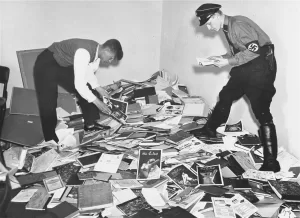

Immediately after taking power in 1933, the Nazis dismantled Germany’s vibrant queer infrastructure. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, the world’s first centre for sexual and gender research and a pioneer of trans healthcare, was destroyed.

In October 1936, Heinrich Himmler created a Reich Central Office for Combating Homosexuality and Abortion. This gave the police powers to jail indefinitely without trial. The regime relied heavily on denunciations from neighbours and colleagues, fostering an atmosphere of suspicion in which queer and trans people were portrayed as deceitful and dangerous.

The persecution was systematic. The Gestapo established the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion, coordinating surveillance, arrests and punishment. Some men were subjected to forced castration or so-called “re-education” in an attempt to eradicate their sexuality; others were sent directly to concentration camps. In Nazi-occupied territories, homosexuals were likewise rounded up and deported.

The history is made more complex by the fact that there were openly queer individuals within early Nazi organisations. Ernst Röhm, co-founder and leader of the SA, was openly homosexual, as were several of his lieutenants. When Röhm’s power became a threat to Adolf Hitler, he was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934. His homosexuality was explicitly cited as justification, signalling that no degree of loyalty could protect queer people once they were deemed inconvenient.

Crucially, the end of the Second World War did not bring an end to this persecution. Paragraph 175 remained in force in both East and West Germany until 1969. Gay men continued to face arrest, imprisonment and social ruin, and many survivors of Nazi camps were too afraid to seek compensation, knowing that doing so would expose them once again to criminalisation.

In the 1970s, activists reclaimed the pink triangle, transforming it from a mark of shame into a symbol of resistance, remembrance and protest against ongoing homophobia. It became a way of forcing public recognition of queer victims of the Holocaust, whose suffering had long been ignored.

Today, the pink triangle carries renewed urgency. Around the world, there are disturbing echoes of the past: the rise of populism and nationalism, appeals to wounded national pride, and the construction of “us versus them” narratives that demonise minorities.

Comparisons between modern immigration enforcement agencies such as ICE and the Gestapo are intentionally provocative, but they reflect a broader concern about unchecked state power and the normalisation of dehumanising rhetoric.

When we see US Department of Labor’s official X account post slogans like “One Homeland, One People, One Heritage” appear, its resemblance to the nazi propaganda poster, which read “Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer” should unsettle us.

Sound familiar?

“One people, one Reich, one Fuhrer.”

“One Homeland. One People. One Heritage.”

And, of course, the people of the United States are NOT one people with one shared heritage.

The diversity of the U.S. is its strength. https://t.co/kjZsI5S9xK pic.twitter.com/2BnygzJn1l

— Chris O’Leary | Catholic Survivor (@IvanDOesnot) January 12, 2026

Holocaust educators remind us that history does not repeat itself exactly, but it does offer warning signs. “Never again” is not a passive slogan; it is a demand for action, whether through protest or solidarity.

In light of Holocaust Memorial Day, queer people across the world are heirs to the pink triangle. It is both our inheritance and our warning, a reminder of where hatred can lead, and a call to ensure that we live through those two words, never again.

© 2026 GCN (Gay Community News). All rights reserved.

Support GCN

GCN is a free, vital resource for Ireland’s LGBTQ+ community since 1988.

GCN is a trading name of National LGBT Federation CLG, a registered charity - Charity Number: 20034580.

GCN relies on the generous support of the community and allies to sustain the crucial work that we do. Producing GCN is costly, and, in an industry which has been hugely impacted by rising costs, we need your support to help sustain and grow this vital resource.

Supporting GCN for as little as €1.99 per month will help us continue our work as Ireland’s free, independent LGBTQ+ media.